Reforming EU Consumer Dispute Resolution for the Digital Age

By: Dori Febler, Read Time: 3 Min

The European Union faces growing pressure to ensure that consumers can resolve disputes fairly and efficiently in an increasingly digital and borderless marketplace. The proliferation of digital services, online transactions, and cross-border purchases has made it difficult for traditional redress methods to keep up with economic and technological advancements. Once hailed as a practical link between consumers and justice, Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) is currently at a turning point. The EU's upcoming ADR framework reform is an ambitious attempt to adjust to a data-driven, global economy while also acknowledging past errors. In light of this, the European Commission's legislative push is part of a larger attempt to restore consumer confidence and regulatory relevance in the digital era, rather than merely updating existing policies.

By: Dori Felber, Read time: 3min

The European Union faces growing pressure to ensure that consumers can resolve disputes fairly and efficiently in an increasingly digital and borderless marketplace. The proliferation of digital services, online transactions, and cross-border purchases has made it difficult for traditional redress methods to keep up with economic and technological advancements. Once hailed as a practical link between consumers and justice, Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) is currently at a turning point. The EU's upcoming ADR framework reform is an ambitious attempt to adjust to a data-driven, global economy while also acknowledging past errors. In light of this, the European Commission's legislative push is part of a larger attempt to restore consumer confidence and regulatory relevance in the digital era, rather than merely updating existing policies.

The European Union is preparing to overhaul its system of Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR), marking a crucial step toward modernising consumer protection for the digital era. A 2025 briefing from the European Parliamentary Research Service (EPRS) on Directive 2013/11/EU highlights the Commission’s proposal to adapt ADR to contemporary market dynamics, cross-border e-commerce, digital content, and global platform economies.

When first introduced in 2013, the ADR Directive was celebrated as a cornerstone of accessible justice, offering consumers an alternative to lengthy and costly court procedures. Yet more than a decade later, its promise remains largely unfulfilled. Only about 5% of consumers who encounter problems turn to ADR because limited awareness, uneven trader participation, and procedural complexity have undermined the system’s credibility. The framework also predates the explosion of digital trade, leaving unresolved how consumers can seek redress for disputes involving digital services or non-EU traders.

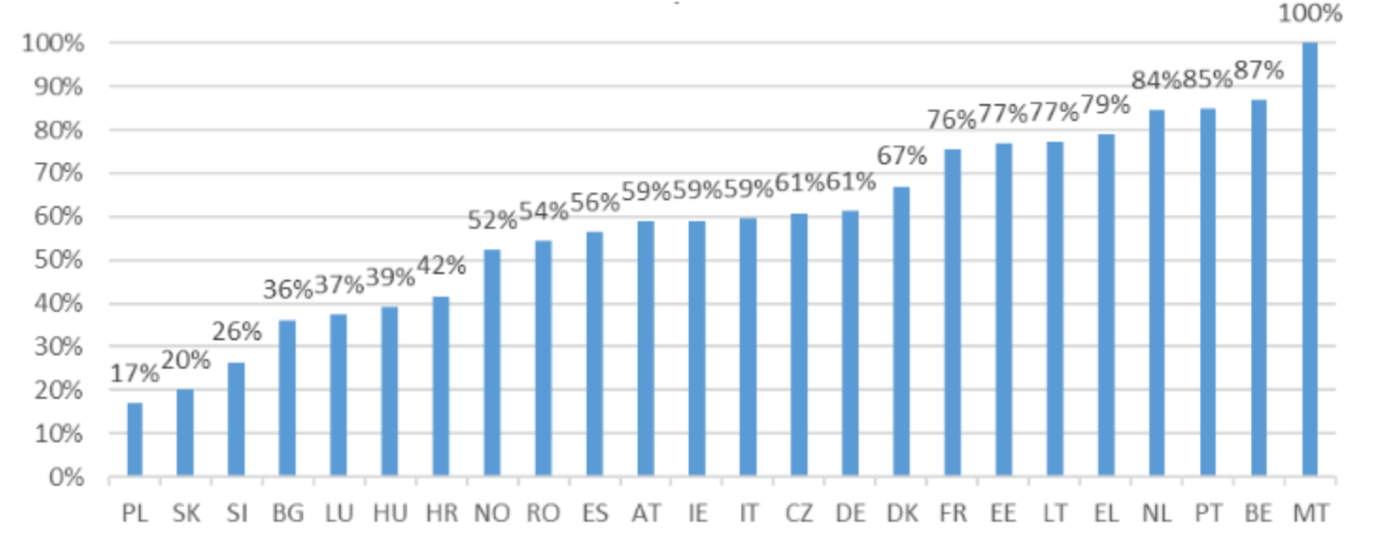

Source: Data collection study: Data for 3 Member States only covered some of the years: BE (based on 2018-2021 data), FR (based on 2019 and 2020 data), and RO (based on 2018-2020 data), Report on the application of Directive 2013/11/EU on alternative dispute resolution for consumer disputes, European Commission, 2023.

The Commission’s 2023 legislative proposal tackles these deficiencies through a sweeping reform. It amends four key directives, on ADR, package travel, consumer enforcement, and representative actions, while repealing the ineffective Online Dispute Resolution (ODR) Regulation. The reform’s aims are clear: make ADR fit for digital markets, boost engagement by consumers and traders, and streamline cross-border resolution procedures.

Expanding Scope and Digitalising Access

The proposal’s most striking feature is its expanded scope. ADR will no longer be confined to contractual disputes but will also cover pre-contractual and non-contractual issues, such as misleading advertising or defective digital products. Moreover, it extends EU consumer protection to transactions involving non-EU traders, asserting the Union’s regulatory reach beyond its borders.

Digitalisation lies at the heart of the reform. New online tools, translation services, and shared data interfaces aim to make ADR faster and more interoperable across Member States. Where automated decision-making is used, consumers must be informed and retain the right to human review, reflecting the EU’s commitment to fairness and transparency in AI-driven systems.

A Test of the EU’s Regulatory Credibility

If successfully implemented, the reform could significantly reduce litigation, improve access to justice, and strengthen trust in the single market. However, its effectiveness will depend on trader participation, enforcement mechanisms for non-EU operators, and sustained consumer awareness.

More than a technical revision, the ADR reform reflects the EU’s ambition to modernise governance through technology without compromising rights. By embedding transparency and digital safeguards into dispute resolution, the Union seeks to transform ADR from a peripheral tool into a central pillar of fair and efficient market regulation.

The reform of the EU’s Alternative Dispute Resolution framework stands as a defining test of the Union’s ability to reconcile technological progress with consumer rights. By extending protection to digital and cross-border transactions, the proposal recognises how profoundly commerce has evolved since 2013 and how urgently policy must evolve with it. Yet the success of this reform will not rest solely on legislative precision but on public trust. Consumers must know that ADR works, and traders must see value in participating. If these conditions are met, the new system could become a cornerstone of accessible justice in the digital age, reinforcing the EU’s credibility as a global standard-setter for fair, transparent, and technology-enabled market regulation.

Part II: From the EU to the world: a journey through the legal bases, historical developments and the current state of EU external action and strategies

By: Antonio Manuel Torres García

The European Union (EU) is oftentimes viewed as an entity that works for the betterment of its members, and while this is largely true, taking into consideration its objectives, values, competences, and means of action, it is nonetheless a narrow view of the wider action the EU undertakes in a more general scene. The position the EU takes when engaging with foreign agents varies according to mutual interests, feasibility, likelihood, and overall net benefit on both sides. But while trade agreements and economic partnership agreements (EPAs) fall within the external action competences the EU enjoys and tend to take the spotlight, they are not the only scenarios in which the EU engages with other states. Separate from the nascent state of a common European defence policy, which represents another facet of the EU action with external effects, European strategies like the Global Gateway mount up to projects comprising initiatives with the aim of tackling the world’s most pressing global challenges; a project that unavoidably carries an explicit “global” approach.

By: Antonio Manuel Torres García, Reading time: 10 min

The European Union (EU) is oftentimes viewed as an entity that works for the betterment of its members, and while this is largely true, taking into consideration its objectives, values, competences, and means of action, it is nonetheless a narrow view of the wider action the EU undertakes in a more general scene. The position the EU takes when engaging with foreign agents varies according to mutual interests, feasibility, likelihood, and overall net benefit on both sides. But while trade agreements and economic partnership agreements (EPAs) fall within the external action competences the EU enjoys and tend to take the spotlight, they are not the only scenarios in which the EU engages with other states. Separate from the nascent state of a common European defence policy, which represents another facet of the EU action with external effects, European strategies like the Global Gateway mount up to projects comprising initiatives with the aim of tackling the world’s most pressing global challenges; a project that unavoidably carries an explicit “global” approach.

This entry represents the second part of the full article. In the first part, which you can easily find on the web under the same title, we dove into the legal basis that allows the EU to carry out specific external actions, in order to understand their relevance. This section carries a different purpose, encompassing firstly a revision of the historical development of EU external actions and overall strategies and, secondly, a consideration of the most recent initiatives, with a view on the shifts they may represent in the grander scheme of things.

The EU external action through the years

The post-colonial birth of EU development cooperation (1957-1975)

The EU’s precursor (the European Economic Community, or EEC) had its first external relations shaped by the colonial ties of several Member States. It is relevant to consider that, even early in its conception, the Treaty of Rome (in its Part IV) covered the association with Overseas Countries and Territories (OCTs), which is still a field of action today. It also covered the creation of the European Development Fund (EDF), which is the predecessor of the modern development instruments, and some early association conventions (Yaoundé Conventions I and II), very relevant in the relations of the EEC with third countries. This first model, however, is one tied to former colonies, not yet global.

The Lomé Conventions (1975-2000)

The most notable examples of the following period are the Lomé Conventions, which introduced a unique and highly ambitious framework with states in Africa, the Caribbean, and the Pacific (ACP) characterised by non-reciprocal trade preferences, a decisive factor in aiding economic development. These Conventions also encompassed a major expansion of EDF volumes, institutionalised political dialogue, and stabilisation schemes (STABEX, SYSMIN). In general, and even before the formal legal bases of development cooperation became explicit in the Treaties, the EU started to behave like a development actor. It can be argued that these conventions influenced the later Article 208 TFEU in substance, and they were relevant in the sense that it now included more countries (46 ACP countries for the first, and 58 in the second iteration) in comparison to the Yaoundé Conventions.

However, it isn’t until the Treaty of Maastricht (1992) that these matters are finally inserted into the Treaties as an explicit EU competence with the predecessors to Articles 208-211 TFEU. It established the primary objective of poverty reduction and the requirement that EU and Member State policies complement each other, representing the beginnings of coherence obligations (anticipating Art. 21 TEU).

The Cotonou Agreement (2000-2020)

Cotonou updates the Lomé model and becomes the legal backbone for development action for two decades. It represented a shift from pure partnership to political conditionality (democracy, rule of law, human rights). We also see the introduction of EPAs and broader and more flexible use of EDF resources, of which it serves as its basis. The Cotonou Agreement, therefore, provided guidance for what would later become Article 21 TEU, while also shaping not only funding but values and conditionality, central to Articles 3(5) and 21 TEU.

Lisbon Treaty (2009)

Picking up where we left off in the legal basis section, there are a few important elements to mention. Firstly, the creation of the European External Action Service (EEAS); secondly, the High Representative’s dual role (Council/Commission); and thirdly, the legal personality for the Union (Article 47 TEU). The CFSP remains intergovernmental, as devised in Maastricht, but development cooperation becomes more coherent. Relevant to consider regarding Lisbon is that it brings together diplomacy and development under one roof, and provides a stronger consistency requirement between internal/external policies. This sets the stage for contemporary external action.

Present’s direct predecessors (2014-2020)

The period encompassing 2014-2020 is one of fragmentation and crisis reaction. Multiple instruments saw the light of day (the Development Cooperation Instrument, the European Neighbourhood Instrument, just to mention a few), contributing to the increased complexity of the EU’s external action, which had been straightforward in comparison. It is also notable that the rise of “crisis-driven” tools, such as the EU Trust Funds (for Syria, Africa, Central African Republic), the creation of the Facility for Refugees in Turkey, and the first European Fund for Sustainable Development (EFSD) is taking place. These situations prompted a growing security-development reciprocal relation that anticipates to an extent the next section: today’s Global Europe.

The 2021 Reform: NDICI-Global Europe and the turn to geopolitics

In the present decade, we have witnessed the consolidation of all the main instruments for external action into the Neighbourhood, Development and International Cooperation Instrument - Global Europe (NDICI - Global Europe), which aims to contribute to the attainment of the objectives agreed upon by the Union, such as the 2030 Agenda and its Sustainable Development Goals, and the Paris Agreement. It is worth noting as well the integration of the EDF into the EU budget and the creation of European Fund for Sustainable Development Plus (EFSD+), a massive investment arm. These steps included a move towards “Team Europe”, and a more strategic, geopolitical framing. In parallel, we see the rise of the European Peace Facility, off-budget and CFSP-related.

The NDICI - Global Europe, established by Regulation (EU) 2021/947, is the central EU funding instrument for relations with third countries in a context of development aid. Framed in the Multi-annual Financial Framework (MFF 2021-2027, which sets the overall ceilings for external spending, it includes geographic programs covering Sub-Saharan Africa, Asia and the Pacific, the Americas and the Caribbean, and countries in the Neighbourhood area, following thematic programs such as human rights and democracy, civil society, peace, stability and conflict prevention, and global challenges (health, climate, education). The NDICI replaces the myriad of instruments previously established in the period from 2014-2020, unifying external action by covering all relevant fields of action and geographical areas under the umbrella of the EU’s values and objectives, which are oftentimes given expression through non-binding instruments like the European Consensus on Development (2017), the EU Global Strategy (2016), and the European Green Deal (2021).

Other non-binding acts, such as the EU Humanitarian Aid Consensus (2007), guide the area of humanitarian aid. This is put into practice by the Council Regulation (EC) No 1257/96 (as amended), which breathes life into the European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations (ECHO), alongside the previously mentioned EPF (Council Decision (CFSP) 2021/509), which funds military assistance and peace support operations in third countries.

Another important part of the recent EU’s shift towards a more unified, expansive, and conditionality-riddled external action is the international agreements governing funding. These also have the force of law and guide EU development funding relationships. In this context, the post-Cotonou agreement (2021) serves as a good example. Successor to the previous Cotonou Agreement, it governs relations with the ACP states more detailedly and binds political, economic, and development cooperation.

So, what can we make up of all this?

Barely a week ago, the EU and the African Union (AU) celebrated their annual summit, this time commemorating the 25th anniversary of their partnership, and signifying the most recent iteration of EU external action. And it’s been quite the ride: the EU first underwent a transformation from post-colonial legacy to self-aware global actor. The EU did not start as a global actor; it became one. Similarly, it went from a partnership rhetoric to conditionality and governance export, shifting from a preferential trade-based partnership model to one marked by political conditionality and the projection of internal commitments. Values once understood as guiding principles internally have gradually become operational instruments externally.

Furthermore, it went from fragmented instruments to consolidation and geopolitics. The creation of the NDICI - Global Europe and EFSD+ is not merely administrative simplification, it represents the EU’s attempt to act with geopolitical coherence in a competitive international environment. The NDICI is more than a budgetary decision. And this is important: the boundary between development cooperation and foreign policy has become increasingly difficult to separate. Once conceived as solidarity, it is now mixed with economic influence, migration management, security concerns, and strategic investments: development, trade, diplomacy, and security now operate in a shared ecosystem.

The EU’s journey in external action also reflects a rebalancing between Member State-driven action and Union-level action. While CFSP retains its intergovernmental character, development cooperation, humanitarian aid, and investment have become increasingly “EU-owned”. Whether this represents genuine transformation or a rebranding of long-standing approaches remains open to interpretation.

All in all, we can say that the evolution of the EU’s external action is marked by a tension between the Union’s commitment to its foundational values and the pragmatic demands of international politics. It is in managing this coexistence of values and interests that the EU cements its international presence and articulates its actions.

Part I: From the EU to the world: a journey through the legal bases, historical developments and the current state of EU external action and strategies

By: Antonio Manuel Torres García

The European Union (EU) is oftentimes viewed as an entity that works for the betterment of its members, and while this is largely true, taking into consideration its objectives, values, competences, and means of action, it is nonetheless a narrow view of the wider action the EU undertakes in a more general scene. The position the EU takes when engaging with foreign agents varies according to mutual interests, feasibility, likelihood, and overall net benefit on both sides. But while trade agreements and economic partnership agreements (EPAs) fall within the external action competences the EU enjoys and tend to take the spotlight, they are not the only scenarios in which the EU engages with other states. Separate from the nascent state of a common European defence policy, which represents another facet of the EU action with external effects, European strategies like the Global Gateway mount up to projects comprising initiatives with the aim of tackling the world’s most pressing global challenges; a project that unavoidably carries an explicit “global” approach.

By: Antonio Manuel Torres García, Reading time: 10 min

The European Union (EU) is oftentimes viewed as an entity that works for the betterment of its members, and while this is largely true, taking into consideration its objectives, values, competences, and means of action, it is nonetheless a narrow view of the wider action the EU undertakes in a more general scene. The position the EU takes when engaging with foreign agents varies according to mutual interests, feasibility, likelihood, and overall net benefit on both sides. But while trade agreements and economic partnership agreements (EPAs) fall within the external action competences the EU enjoys and tend to take the spotlight, they are not the only scenarios in which the EU engages with other states. Separate from the nascent state of a common European defence policy, which represents another facet of the EU action with external effects, European strategies like the Global Gateway mount up to projects comprising initiatives with the aim of tackling the world’s most pressing global challenges; a project that unavoidably carries an explicit “global” approach.

In this first part of the article, we will dive into the legal basis allowing the EU to carry out specific external actions, in order to understand their relevance. In the second part of the article, which will be published soon, we will revisit the historical development of these actions and, finally, consider the most recent initiatives, with a view to the shifts they may represent in the broader context.

The EU: an integrated actor in the international scene by default

The fact that the EU is a product of international cooperation is undebatable. However, what once started with more of an inward-looking approach, such as security and economic integration of its members, quickly widened its scope and areas of action, updating its means and competences in tune with contemporary challenges and opportunities. It is in this context of expansion and development that the EU is conferred larger powers and solidifies its presence in the international arena. The EU has legal personality (Art. 47 TEU) and areas of competence in which to engage in cooperation with other international organisations or states. To this end,several provisions in its founding Treaties regulate these matters.

One of these notable provisions is Art. 3(5) TEU, which establishes the general approach the EU must take in its relations with the wider world, whose objectives can be identified as the contribution to peace, security, sustainable development, solidarity, and mutual respect among peoples globally. This provision represents the general picture in which other operative elements must abide by.

Under Title V of the TEU we can find the general principles and objectives of the EU’s external action, forming the core foundation for EU policies in relation to third countries and other legal entities. In this sense, Art. 21 TEU further deepens the previously mentioned article by fleshing out more specifically the objectives, principles, and values the EU must respect and abide by in its external action. Among these, we can find the consolidation of democracy, rule of law and human rights, sustainable economic, social, and environmental development, and poverty eradication, alongside others. It must be noted that it requires the consistency of external actions with internal policies, setting an order for coherence and rationality.

Art. 22 TEU further outlines the creation of strategies for external action and defines the pivotal role the European Council (EuCo) represents as a guiding force. Articles from 24 to 46 TEU comprise the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) provisions, collecting the specific means, areas of action and the roles of the relevant actors, such as the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, the Commission, the Council of the EU, the Member States and, as mentioned, the EuCo. It is relevant to mention the exclusion of the Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU) jurisdiction specifically in CFSP matters, and the role that the Council of the EU plays as the institution of utmost importance in this context, a legacy architecture stemming from the pre-Lisbon system of pillars whose main trait was its intergovernmental nature.

These provisions are further complemented by the more specific nature of the relevant articles found in the TFEU. It is in this text that we may find the more practical approach of what the TEU puts forward. In this spirit, Articles 208-211 TFEU group the development and cooperation provisions, whose main objective is the reduction and eradication of poverty. It specifies that the EU development policy must be complementary to Member States’, and it allows the EU to sign agreements with countries that may benefit from cooperation in the field of development.

In the same light, Article 212 TFEU relates to economic, financial, and technical cooperation, enabling wider cooperation beyond traditional development aid, and Article 213 TFEU, which allows for emergency financial assistance to third countries. In the field of humanitarian aid, Article 214 TFEU grants ad hoc assistance following the principles of neutrality, impartiality and non-discrimination to third countries in need. Finally, Article 215 TFEU provides for restrictive measures, serving as the basis for sanctions and certain crisis-response funding mechanisms.

It is worth mentioning that the EU’s external action underlying architecture refers back to Art. 2 TEU, which contains the foundational values of the Union and, in this context, works as the guiding concepts that every initiative must strive towards. Despite not being the topic of the present article, it must be noted that the general structure of the EU’s external action may represent current-times neocolonialism, by exporting values that may not be common outside the Union.

Taking the aforementioned into account, it is undeniable that the EU enjoys a fair margin of operation when it comes to external action. With time, it has become the depository of determined competences to undergo projects and schemes, be it in a more independent manner or in a closer cooperation with its Member States, with third countries.

In the second part of the article, we will zoom in on past experiences and strategies, without which the present landscape can’t be properly understood, and assess contemporary approaches.

Climate Change in Times of Rearmament - How Green Can Defense Really Be?

By: Anneke Pelzer, Reading time: 4 min

When Greta Thunberg stood up at the podium at the UN Climate Action Summit in 2018 and spoke her famous words „How dare you?“ over and over again, she was trying to get the world’s political elite to take action against mankind’s greatest threat, climate change. Today, in 2025, frustratingly little progress has been made. Instead, it seems like other problems and crises have always been more important. The covid pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine have both challenged European economies unexpectedly, which has led to the postponing of efficient measures to lower the European Union’s (EU) greenhouse gas emissions. Existing goals like the EU becoming climate-neutral by 2050 or the 2015 Paris Treaty limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees celsius get increasingly unreachable as more time without action passes. In the present day, European member states’ worries mostly revolve around protection of Europes’ borders, which has caused military spending to have reached a new high in the EU. With rearmament’s new importance, the question arises as to how the EU wants to include its new focus on military advances in its climate goals.

By: Anneke Pelzer, Reading time: 4 min

www.esercito.difesa.it, CC BY 2.5 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5>, via Wikimedia Commons

When Greta Thunberg stood up at the podium at the UN Climate Action Summit in 2018 and spoke her famous words „How dare you?“ over and over again, she was trying to get the world’s political elite to take action against mankind’s greatest threat, climate change. Today, in 2025, frustratingly little progress has been made. Instead, it seems like other problems and crises have always been more important. The covid pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine have both challenged European economies unexpectedly, which has led to the postponing of efficient measures to lower the European Union’s (EU) greenhouse gas emissions. Existing goals like the EU becoming climate-neutral by 2050 or the 2015 Paris Treaty limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees celsius get increasingly unreachable as more time without action passes. In the present day, European member states’ worries mostly revolve around protection of Europes’ borders, which has caused military spending to have reached a new high in the EU. With rearmament’s new importance, the question arises as to how the EU wants to include its new focus on military advances in its climate goals.

Dirty militaries

Before Russia’s invasion and Europe’s wake from its pre-crisis hibernation, all military sectors of Europe combined produced around 25 million tonnes of CO2 in 2019. Internationally, the military sector is responsible for an astonishing 5,5 percent of all greenhouse gas emissions. Europe will not reach its goals written down in the European Green Deal and neither will the world meet their limit of stopping global warming at 1,5 degrees Celsius if military and defense measures are not taken into account. This lack of measures to prevent military-related emissions is illustrated by the fact that the European Climate Law, which sets the goal of climate-neutrality by 2050, does not apply to military. In the 2015 Paris Climate Treaty, military emissions that are produced abroad are excluded as well. Additionally, EU-NATO members have reported collective emissions of 6,9 million tonnes in 2021, but according to the Conflict and Environment Observatory, a much bigger reporting gap has to be expected. These findings entail that military greenhouse gas emissions remain largely unreported and therefore opaque.

New Challenges

Global warming being the greatest threat to mankind, it is time it gets recognized for what it is: a phenomenon as dangerous as military threats from other countries. Europe needs to be able to also defend itself against global warming, which makes change inevitable. Militaries need to begin ensuring that they will also be able to operate in catastrophic weather events that will occur more often and how they can adapt to function under new environmental challenges. Aside from that, emissions caused by militaries need to be included in agreements like the European Green Deal to start to get countries thinking about how they can use new green technologies for defense purposes. At the moment, too little renewable resources are being used in defense. Militaries still greatly rely on fossil fuels, such as gas and oil. Not only is the usage of those energy sources preventing the EU from meeting its climate goals, but it also makes Europe’s armies dependent on powers like Russia. Relying on fossil fuels will also only get more expensive over the next decades as those resources will get less available.

Setting off towards a greener future

On the way to more sustainable European armies, one of the key factors will be the efficient use of energy and natural resources. In March 2022, the EU launched a Climate Change and Defense Roadmap. It recognizes the instability climate change will cause and the military risks it will bring. Furthermore, it states that the „armed forces need to invest in greener technologies throughout their inventory and infrastructure“, which is to be implemented in the Common Security and Defense Policy. 133 million euros were made available in the European Defense Fund Work Programme to develop solutions for sustainable and efficient use of energy, reduce energy consumption, and make military mobility more sustainable. With help of instruments like PESCO, where member states collaborate on improving defense, and the European Defense Fund, the EU sets out to „boost technological innovation to make military equipment more efficient and less reliant on fossil fuels“.

The European states are desperate for solutions; otherwise, they will risk their competitiveness in the future. Current crises might hold a potential for getting Europe on the right path. With record investments, it would also be possible to put a greater focus on greener inventions and steer Europe's armies in a more sustainable direction. The question that remains is whether the EU recognizes this potential, and if it continues to be willing to accept higher spending on green defense and the training that comes along with the new technologies.

Boardrooms in Balance: Why Gender Diversity is Now a Governance Must

By: Dori Felber, reading time: 4 minutes, 58 seconds

Ensuring balanced representation on corporate boards has moved from a mere social objective to a legal and governance priority across the EU. On 17 October 2022, the Council adopted its final text on gender balance in the corporate boards of listed companies (Directive 2022/238). How did this Directive impact corporate governance? In order to answer such a question, it is first necessary to outline what the Directive entails: its objectives, policy background and scope. Only then can we meaningfully assess its legal and practical implications for corporate governance across Member States.

By: Dori Felber, reading time: 4 minutes, 58 seconds

Ensuring balanced representation on corporate boards has moved from a mere social objective to a legal and governance priority across the EU. On 17 October 2022, the Council adopted its final text on gender balance in the corporate boards of listed companies (Directive 2022/238). How did this Directive impact corporate governance? In order to answer such a question, it is first necessary to outline what the Directive entails: its objectives, policy background and scope. Only then can we meaningfully assess its legal and practical implications for corporate governance across Member States.

All about Directive 2022/238

Equality of treatment and opportunities between women and men is among the principles set out in the Treaties of the EU, and after the harrowing figures published in 2022, revealing that only 32.2% of board members and a mere 8% of board chairs were women, underscored the persistent gender imbalance in corporate leadership. These statistics have made it evident that concrete steps must be taken in order to “help [to] remove the obstacles women often face in their careers”. Thus, the primary objective of Directive 2022/238 is to achieve a more balanced representation of women and men among directors in listed companies by increasing transparency and accountability, as well as by imposing binding quantitative gender‐representation targets for boards. The Directive will apply to listed companies with registered offices in EU Member States, requiring them to have at least 40% of their non-executive director positions or 33% of their non-executive and executive director positions held by women by 2026.

How does this link to corporate governance?

The growing emphasis on board diversity extends beyond the pursuit of social equality. Corporate governance also closely interconnects with board diversity, with three main logics shaping how the two interact. Regulators and policymakers now treat board composition as a risk-management and oversight issue. According to the OECD, female directors bring more independent views into the boardroom and strengthen its monitoring function by counteracting groupthink. More diverse boards promote a wider range of perspectives, thereby reducing groupthink and improving the monitoring of management and risk oversight, ultimately enhancing corporate governance overall. Both the OECD and the Commission cite evidence that quotas, disclosures, transparency and other measures substantially increase the representation of women on corporate boards, as well as their effectiveness.

Continually, investors and financial markets have increasingly viewed gender-balanced boards as a core element of good corporate governance, rather than a mere social issue. Large investors and investment advisors such as BlackRock, as well as ESG frameworks, have continuously pushed for better board composition as part of the fiduciary assessment of long-term value and governance quality. This means that boards that ignore diversity risk negative votes, reputational damage, or even tougher scrutiny during capital raises.

The third governance logic behind board diversity is business performance, although debated, it still remains relevant in governance circles. Major empirical reviews reveal a favourable relationship between diverse leadership teams and financial outperformance for many organisations, and policymakers cite these findings to argue that board diversity promotes long-term corporate performance. That economic framing pushes diversity into board agendas as a criterion of effective governance, rather than just justice. There remains ongoing academic debate regarding the causation and robustness of these findings; nonetheless, McKiney represents the mainstream practitioner position, whilst the OECD provides a broader policy synthesis.

The EU Directive 2022/2381 marks a defining moment in the evolution of European corporate governance. What began as an equality measure has evolved into a governance reform that incorporates diversity into the core values of board responsibility, openness, and strategic oversight. The Directive's ultimate impact, however, will be determined by how companies internalise these obligations: whether they view gender balance as a compliance checkbox or an opportunity to transform decision-making culture and long-term resilience.

THE EXCESSIVE FLEXIBILITY OF THE WORKING TIME DIRECTIVE AND ITS INADEQUACY IN PROTECTING WORKERS AFTER THE GREEK REFORM

By Aurora Dagnino, reading time: 5 minutes and 45 seconds

Greece's parliament approved a few weeks ago a contested labour bill that would allow 13-hour workdays, despite strong opposition from labour unions, opposition lawmakers, and civil society groups, all of whom argued that the measure undermines worker protections. Two nationwide strikes were held in the space of two weeks from early October, paralyzing the country. In both Athens and Thessaloniki, transportation networks were shut down, while hospital staff, teachers and other civil servants stopped working.

By Aurora Dagnino, reading time: 5 minutes and 45 seconds

Greece's parliament approved a few weeks ago a contested labour bill that would allow 13-hour workdays, despite strong opposition from labour unions, opposition lawmakers, and civil society groups, all of whom argued that the measure undermines worker protections. Two nationwide strikes were held in the space of two weeks from early October, paralyzing the country. In both Athens and Thessaloniki, transportation networks were shut down, while hospital staff, teachers and other civil servants stopped working.

Workers’ protest, BBC: Greece passes labour law allowing 13-hour workdays in some cases

Under the new law, workers in certain sectors, such as manufacturing, retail, agriculture, and hospitality, could work for up to 13 hours per day, but only for a limited number of days each year: 37. Employees will remain bound by an overall cap of 48 working hours per week, calculated on a four-month average, with the general 40-hour workweek continuing as the standard. The total annual overtime permitted continues to be 150 hours, and workers performing overtime will receive an additional 40 percent on top of their regular wages. The government has highlighted that participation in the 13-hour schedule will be strictly voluntary and subject to the employee’s consent.

This new law comes with no surprise, and it seems to reflect a trend that goes in the opposite direction with the rest of Europe, where an increasing number of countries are reducing the working week. In 2024, Greece introduced a six-day working week for certain industries to try to boost economic growth.

The legislation, which came into effect at the start of July, allows employees to work up to 48 hours in a week as opposed to 40. It must be said that it only applies to businesses which operate on a 24-hour basis and is optional for workers, who get paid an extra 40% for the overtime they do.

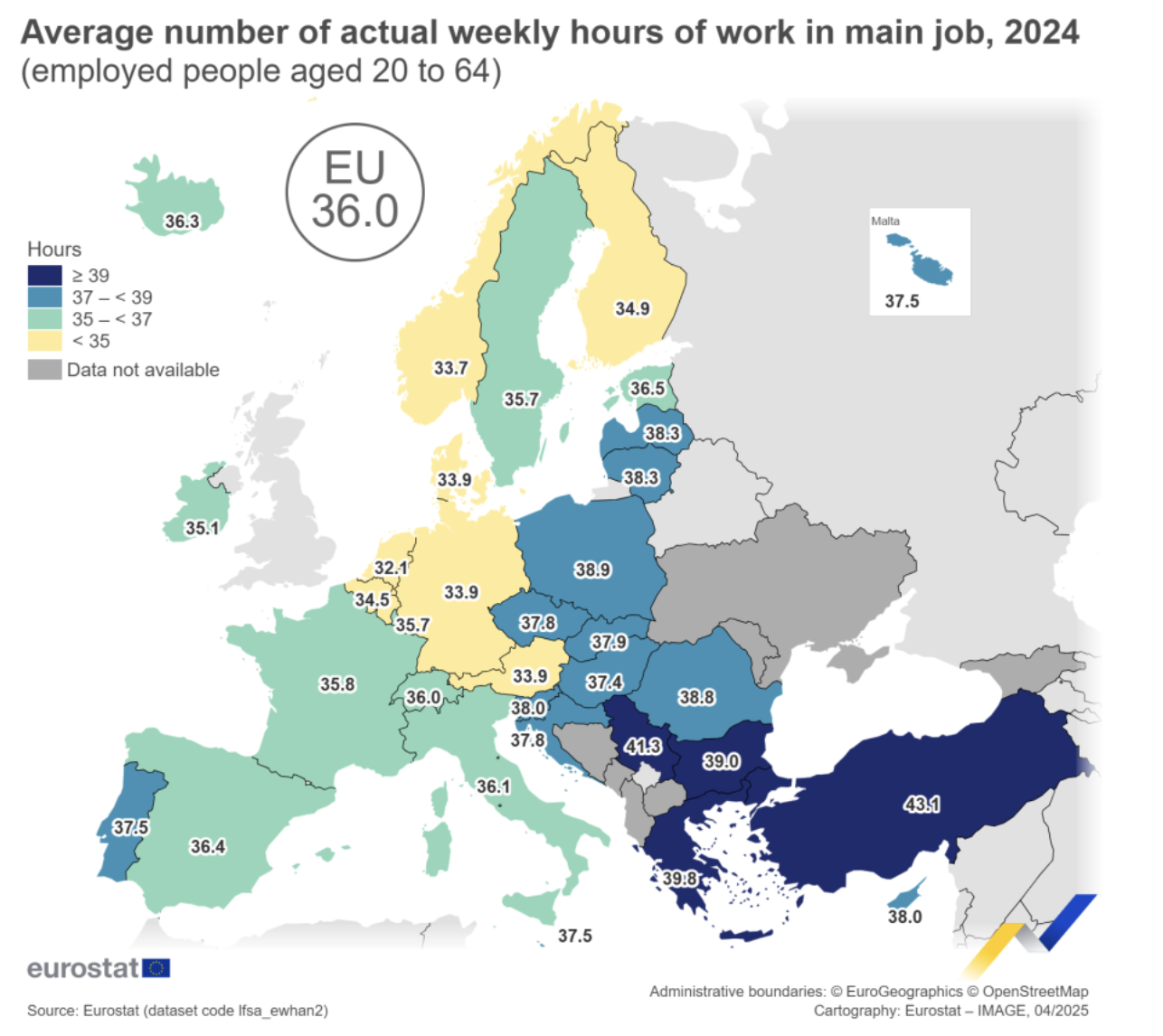

In 2024, the average working week at EU level lasted 36.0 hours. This varied across the EU, from 32.1 actual hours of work in the Netherlands to 39.8 in Greece, showing the Greek contradictory trend.

But what does EU law say about this? Is there any limit on the maximum duration of a working day?

The relevant piece of legislation here is the Directive 2003/88, hereinafter called “working time directive”. The aforementioned does not explicitly establish how long a working day could be, but it could be derived implicitly. Let’s take a look at the relevant articles:

Article 3 defines daily rest and establishes that every worker is entitled to a minimum daily rest period of 11 consecutive hours per 24-hour period.

Article 4 disciplines breaks, entitling workers to a rest break after 6 hours of work.

Article 5 regulates the weekly rest period, granting workers a minimum uninterrupted rest period of 24 hours plus the 11 hours' daily rest referred to in Article 3.

Article 6 is also relevant, which limits average weekly working time (including overtime) to 48 hours. This limit is calculated over a reference period (usually 4 months)

From this we can determine that the maximum duration of a working day is 13 hours (24h - 11h rest); therefore, legally speaking, the Greek government has not breached any EU law.

Moreover, under Article 17, derogations from the daily rest period (Article 3) and breaks (Article 4) can be implemented in activities involving the need for continuity of service or production. Thus, by applying the 13 hours only to certain sectors, Greece acted fully within the boundaries of the working time Directive.

But is a 13 hour day really doable? Where is the respect for social and private life? Is it beneficial for the productivity of the worker? It goes without saying that working for 13 hours is hardly tenable, both from a physical and psychological point of view.

Furthermore, the argument that there is no obligation on the worker and that participation is voluntary is not realistically applicable in the labour scenario, where we have an asymmetry of power between the employee and the employer.

As if this wasn’t enough, Article 22 of the Directive, allows Member States not to apply the standard maximum limit on weekly working time. Through this opt-out mechanism, EU Member States can require workers to agree to work more than 48 hours over a seven-day period.

It is for these reasons that the Directive should explicitly put a ceiling on the duration of the working day, avoiding granting so much flexibility to employers, both in terms of the duration of the working day but also the duration of the breaks.

Another point of criticism of the Directive is that it does not specify whether the working time limit should apply per worker (covering all jobs held by an individual) or per contract (applying limits separately to each job). If the primary goal is protecting the health and safety of workers, it should apply per worker; however, many Member States applied it per contract.

The Directive has been additionally attacked because it does not adequately define how on-call duty should be treated, meaning periods when a worker is required to be available for work, but not necessarily working the entire time. An example is a doctor who must stay at the hospital overnight in case of emergencies or a firefighter who must be ready to respond immediately, even if resting at the station.

The issue here are the vague definitions in article 2 of "working time" and "rest period": working time is defined as "any period during which the worker is working, at the employer's disposal, and carrying out his activity or duties"; while rest period is defined simply as "any period which is not working time".

Ergo, the Directive failed to address the time spent on-call, which often involves long periods of inactivity combined with the requirement to be available. While the legislation is uncertain on this merits, the CJEU has already clarified the point, but legislative attempts to amend the Directive to counter these rulings have failed.

In the SIMAP Case (C‑303/98, 2000) the CJEU consistently ruled that inactive time spent on-call at the workplace must be counted as working time in its entirety. Despite the clear CJEU ruling, compliance and interpretation across Member States remain problematic: in some Member States, only active on-call duty at the workplace is counted as working time (e.g., Poland and Slovenia). Similarly, in Slovakia, on-call duty at the workplace does not fully count as working time for certain groups.

More than 20 years after its entry into force, the Directive is clearly unfitted to regulate nowadays working dynamics and suffers from being too vague and flexible. It leaves important, basic issues unaddressed, which has led to persistent legal confusion and fragmented practice among Member States. Moreover, its full application can be avoided through opt-outs and derogations, putting at risk the health and safety of workers, which should be the primary aim of the Directive, but which in practice is often not achieved.

How the EU does(n’t) fight gender-based violence

By Anna-Magdalena Glockzin, 5 minutes.

In July 2019, an 18-year-old British woman went to the Cypriot police, and told them, that she had been raped by a group of 12 Israeli men in Ayia Nap. The Cypriot authorities questioned her for hours without legal assistance, which subsequently led her to withdraw these allegations. The woman later stated that she was pressured to comply and had to sign a waiver, which was drafted by Cypriot detectives. In the following proceedings, the Cypriot authorities found her guilty of lying about the gang rape attack, convicted her of causing public mischief, and issued a suspended sentence of four months. With the help of the human rights group Justice Abroad, the woman appealed to the Court of final instance, the Supreme Court of Cyprus, which overturned the verdict. It found that the woman did not receive a fair trial. The authorities, however, never admitted to any wrongdoings. This case caused outrage among women’s rights activists, who argued that the woman was treated as the offender rather than the victim.

By Anna-Magdalena Glockzin, 5 minutes.

In July 2019, an 18-year-old British woman went to the Cypriot police, and told them, that she had been raped by a group of 12 Israeli men in Ayia Nap. The Cypriot authorities questioned her for hours without legal assistance, which subsequently led her to withdraw these allegations. The woman later stated that she was pressured to comply and had to sign a waiver, which was drafted by Cypriot detectives. In the following proceedings, the Cypriot authorities found her guilty of lying about the gang rape attack, convicted her of causing public mischief, and issued a suspended sentence of four months. With the help of the human rights group Justice Abroad, the woman appealed to the Court of final instance, the Supreme Court of Cyprus, which overturned the verdict. It found that the woman did not receive a fair trial. The authorities, however, never admitted to any wrongdoings. This case caused outrage among women’s rights activists, who argued that the woman was treated as the offender rather than the victim.

The European Court of Human Rights intervenes

To answer this public outrage and following the Cypriot attorney general’s decline to reopen the investigations, the case got referred to the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR). On the 27th of February 2025, the ECtHR concluded that the Cypriot authorities mishandled the case. The Court held that the authorities “failed in their obligation to effectively investigate the applicant’s complaint of rape and to adopt a victim-sensitive approach when doing so.” In particular, it stated that the Cypriot authorities breached article 3 (lack of effective investigation) and article 8 (the right to respect for private and family life) of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR).

Moreover, the ruling highlighted that “neither the chief investigator nor the counsel for the Attorney General […] engaged in any meaningful examination of the evidence which could signify a lack of consent.” Hence, this case unveils how deeply embedded prejudices against rape victims are in the (Cypriot) law enforcement system. Significantly, this discrimination is rooted in the dominant presence of patriarchal structures and practices, like victim-blaming. Furthermore, it demonstrates the importance of procedural protection for victims of gender-based violence. Shifting the focus to the level of the European Union (EU), this raises the following questions: How does EU legislation aim to protect women, girls and other marginalized groups from sexual violence? And where does it fall short?

Protest to end violence against women

By Fmtechgirl - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=46937216

Legislation concerning gender-based violence in the European Union

To tackle the problem of gender-based violence in the EU, the European Commission proposed a Directive in March 2022. Based on this initiative, the European Parliament approved the EU Directive 2024/1385 on combating violence against women and domestic violence, which was adopted by the Council in May 2024. Member States are bound to fully implement the Directive by June 2027. Its articles define different forms of violence (online and offline) against women as crimes. These include female genital mutilation and forced marriage, non-consensual sharing of intimate pictures, cyber stalking, cyber harassment and incitement to hatred, and violence on the ground of gender. Furthermore, the Directive lays out specific measures to protect and support victims of gender-based violence as well as providing and enhancing access to justice. Lastly, it obliges Member States to set forth preventive measures, particularly those which aim to prevent rape and emphasize consent in sexual relationships.

Furthermore, in 2017, the Union joined the Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence, also known as the Istanbul Convention, which went into force in 2023. It obliges members to implement laws, policies and support services to fight violence against women and girls. Moreover, the Commission’s Gender Equality Strategy 2020-2025, prioritizes combating gender-based violence, which Commission President Ursula von der Leyen reiterated in her letter to the new Commissioner for Equality for a gender equality strategy post-2025. Lastly, the EU dedicated the 25th November as the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women, on which the European Commission and the EU High Representative of Foreign Affairs hold a speech together.

There is still room for improvement

However, several hurdles in the EU’s fight against gender-based violence persist to this day. For instance, the collection of statistical data does not cover all 27 Member States. The EU survey on gender-based violence collects only data from 18 EU countries. For the remaining countries, the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE) and the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) coordinate the data collection. In November 2024, Eurostat, EIGE and FRA published a report together for the first time, combining the data and providing an overview of women’s experiences with regards to violence in the whole of the EU. Nonetheless, the non-cohesiveness of the data continues to be a problem as well as the limited scope of the EU survey.

Furthermore, neither the Directive mentioned above nor any other EU document establishes an EU-wide (consent-based) definition of “rape” and “sexual assault”, exacerbating problems of discriminatory treatment in judicial processes and impunity of perpetrators. While the different criminal codes of the Member States do not provide a common definition of these crimes, it should and must not serve as an excuse for failing to establish respective legal definitions at the EU level. Gisèle Pelicot’s deeply shocking case in France and the case of the British woman in Cyprus, among many others, reveal that the fight against gender-based violence is far from over. This underscores the urgent need to induce fundamental and lasting change in society, policymaking, legislation and judicial processes, ensuring the protection and equality of women and girls.

EU drops AI Liability Directive: What it means for regulation and innovation

By Anni Rissanen. Read: 1 min 54 s

The European Commission has decided to withdraw a key proposal that would have made it easier to hold companies accountable for AI-related harm. Some say it is a win for innovation, while others warn it creates a legal mess. What happens next for AI regulation in Europe?

Gisele Pélicot is a survivor of a series of rape, orchestrated by her husband Dominique Pélicot. Over a period of 9 years (July 2011 to October 2020) Gisele Pélicot was repeatedly raped by her husband and individuals who he would invite, whilst she was drugged and unconscious. In total, Gisele Pélicot was raped 92 times by 72 men, as her husband filmed the abuse. These horrific acts came to light when Dominique Pélicot was arrested by the police for taking upskirt photographs of women in supermarkets. The police discovered thousands of images and videos that Pélicot had taken of the rapes and stored on his computing equipment. Pélicot is further accused of training Jean-Pierre Maréchal on how to drug and rape his own wife.

By Anni Rissanen. Read: 1 min 54 s

The European Commission has decided to withdraw a key proposal that would have made it easier to hold companies accountable for AI-related harm. Some say it is a win for innovation, while others warn it creates a legal mess. What happens next for AI regulation in Europe?

The European Commission has decided to withdraw its proposed AI Liability Directive, triggering strong reactions across the political spectrum. This Directive was expected to create a clearer framework for holding companies accountable for AI-related harm. However, its withdrawal raises key questions about how AI liability will be regulated in Europe, namely who will be responsible when AI causes harm, how victims can seek compensation, and whether existing national laws are sufficient to address emerging AI risks.

Mixed reactions in the Parliament

Many in the European Parliament have criticized the decision. Axel Voss (EPP), who led work on the Directive, warned that scrapping it creates ‘legal uncertainty’ because without a common EU-wide framework, AI-related liability will be handled differently in each of the 27 Member States. This means companies and individuals will have to navigate a patchwork of national laws, making it harder to seek compensation for AI-related harm and potentially discouraging smaller businesses from developing AI technologies. Others, including Aura Salla (EPP, Finland), welcomed the decision, arguing that the Directive was flawed and unnecessary. The Socialists & Democrats (S&D) and Greens also voiced concerns, stressing the need for strong AI accountability mechanisms.

Support from governments and the tech industry

The withdrawal, however, was met with approval from EU member states and tech industry groups. Poland and France backed the decision, favoring deregulation over added liability rules. CCIA Europe, which represents major tech firms, praised the move as a win for innovation, arguing that excessive regulation could stifle progress.

The reason behind the withdrawal of the Directive

The Commission cited a lack of political consensus as the main reason for shelving the Directive. Trade Commissioner, Maroš Šefcovic, acknowledged that negotiations had stalled but hinted that a revised approach to AI liability could emerge later in the future. Notably, the European Parliament’s legislative portal remains open for amendments, suggesting that the debate is not entirely over.

What is next for AI regulation?

With this AI Liability Directive off the table, the focus now shifts to how AI liability will be handled across Europe. Will existing regulations, like the AI Act, be enough to ensure accountability? Or will new proposals emerge to bridge the gaps?

For now, the Commission appears to be prioritizing competitiveness and innovation, potentially signaling a shift toward a more flexible regulatory approach. Whether this fosters progress or leaves critical gaps in consumer protection remains to be seen.

Why the Gisele Pelicot case calls for a redefinition of rape in France

By Dori Felber. Read: 3 minutes 42 seconds

Time to redefine the outdated definition of rape in France? As the horrific testimony of Gisele Pélicot unfolds, many have argued for a redefinition of rape in France. This specifically followed after lawyer Guillaume de Palma, who is defending 6 of the accused, argued that “In France proof of intent is required” in order for it to qualify as rape.

Gisele Pélicot is a survivor of a series of rape, orchestrated by her husband Dominique Pélicot. Over a period of 9 years (July 2011 to October 2020) Gisele Pélicot was repeatedly raped by her husband and individuals who he would invite, whilst she was drugged and unconscious. In total, Gisele Pélicot was raped 92 times by 72 men, as her husband filmed the abuse. These horrific acts came to light when Dominique Pélicot was arrested by the police for taking upskirt photographs of women in supermarkets. The police discovered thousands of images and videos that Pélicot had taken of the rapes and stored on his computing equipment. Pélicot is further accused of training Jean-Pierre Maréchal on how to drug and rape his own wife.

By Dori Felber, Read: 3 minutes 42 seconds

Time to redefine the outdated definition of rape in France? As the horrific testimony of Gisele Pélicot unfolds, many have argued for a redefinition of rape in France. This specifically followed after lawyer Guillaume de Palma, who is defending 6 of the accused, argued that “In France proof of intent is required” in order for it to qualify as rape.

Gisele Pélicot is a survivor of a series of rape, orchestrated by her husband Dominique Pélicot. Over a period of 9 years (July 2011 to October 2020) Gisele Pélicot was repeatedly raped by her husband and individuals who he would invite, whilst she was drugged and unconscious. In total, Gisele Pélicot was raped 92 times by 72 men, as her husband filmed the abuse. These horrific acts came to light when Dominique Pélicot was arrested by the police for taking upskirt photographs of women in supermarkets. The police discovered thousands of images and videos that Pélicot had taken of the rapes and stored on his computing equipment. Pélicot is further accused of training Jean-Pierre Maréchal on how to drug and rape his own wife.

It is the State’s responsibility to prosecute sexual assault offences as a grave and systematic violation of human rights, and in order to do so, a comparison and evaluation must be made between the laws that are in place for rape in France (who has ratified the Convention) against the criteria set out in the Istanbul Convention. The above-mentioned Convention is the first instrument in Europe that sets out legally binding standards for the laws and procedures that are in place for such crimes, created with the intention to protect the victims and adequately punish the perpetrators.

The definition of rape is detailed in Article 36 (a) (c) of the Istanbul Convention as the following:

a. Non-consensual vaginal, anal or oral penetration of a sexual nature of the body of another person with any bodily part or object;

c. Causing another person to engage in non-consensual acts of a sexual nature with a third person.

It further states that consent must be given voluntarily, which will be assessed according to the circumstances of the case (Article 36 (2)), and that this offence includes former or current partners and spouses (which are recognised by national law) (Article 36 (3)). Thus, the relationship between the victim and the perpetrator does not matter (Article 43). Lastly, Article 46 explains that, if applicable, additional aggravating conditions must be applied. This includes offence committed against a current spouse or committed against a person made vulnerable due to specific circumstances.

Article 222-23 of Code Pénal Français details that rape is any act of sexual penetration, of whatever nature, or any oral-genital act committed on the person of another or on the person of the perpetrator by violence, constraint, threat or surprise. Upon comparison, it is immediately visible that the above-mentioned definition does not include the word ‘non-consensual’. The definition detailed above gives room for argument as to whether the offence constituted rape. The Istanbul Convention details that definitions of sexual assault offences must protect the victims to the fullest extent. The missing element of consent in the definition of rape lacks such a protection. Furthermore, stating that ‘rape is any act of sexual penetration committed by violence, constraint, threat or surprise’ conveys the idea that there needs to be intention. All of the above-mentioned acts necessitate pre-meditated intention. In order to threaten someone, one must know what they are threatening the victim for. This is equally true for constraint, violence and surprise. Consequently, the Article 222-23 necessitates pre-meditated intention for rape. Consequently, such a definition leaves room for lawyers such as Guillaume de Palma to argue that if there is no intention, there is no rape. From this, it is visible that the inclusion of consent in the definition of rape makes the protection of victims unequivocal. Lack of consent, for whatever reason, equals rape.

In conclusion, when evaluating the definition of rape in France against the legal standard provided for by the Istanbul Convention, it is clear that France must redefine their definition of said offence in order to provide adequate protection for the victims and to sufficiently prosecute and punish the perpetrators.

The new European Commission’s Environmental Crime Directive (ECD).

By Yana Chakarova, 7 minutes.

On the 27th of February 2024 the European Parliament adopted a number of revolutionary environmental measures enshrined in the Environmental Crimes Directive that penalized environmental crimes much more stringently compared to the past. The Greens/EFA Group from the European Parliament called for the establishment of a serious criminal liability in the case of destruction or widespread and substantial damage which is long-lasting or irreversible to an ecosystem, a habitat or the quality of air, soil or water. More specifically, the MEP of the Greens/EFA Group stated that:

On the 27th of February 2024 the European Parliament adopted a number of revolutionary environmental measures enshrined in the Environmental Crimes Directive that penalized environmental crimes much more stringently compared to the past. The Greens/EFA Group from the European Parliament called for the establishment of a serious criminal liability in the case of destruction or widespread and substantial damage which is long-lasting or irreversible to an ecosystem, a habitat or the quality of air, soil or water. More specifically, the MEP of the Greens/EFA Group stated that:

‘This new directive is a victory for the environment (...). The outdated 2008 directive needed to be revised as a matter of urgency. With this new text, the EU is adopting one of the world's most ambitious pieces of legislation to combat environmental crime. It will allow for a more effective and better protection of individuals who suffer as a result of such damage. The perpetrators of these crimes will therefore be prosecuted and punished more severely in the case of ‘qualified offences’, which encompass conduct comparable to ecocide. We also welcome the increase in the level of penalties and the introduction of significant additional sanctions (...).’

The global increase in environmental crime, ranging from 5% to 7% annually, is causing enduring harm to ecosystems, wildlife, human health, and the finances of both governments and businesses. As per estimates from UNEP and Interpol released in June 2016, the yearly financial impact of environmental crime is estimated to be between $91 billion and $258 billion. Despite this, the number of convictions for environmental crimes has not increased substantially.

The new directive clarifies to the Member States the definition of environmental offences and the punishment the offenders would suffer as a result. The new directive categorizes breaches of environmental obligations like illegal trade, handling of chemicals or mercury, and illegal ship recycling as criminal offences. The severity of punishment for offences related to illegal waste collection, transport, treatment, or the unauthorized sale of timber or timber products derived from illicitly harvested wood will not significantly vary between legal entities and individuals. Consequently, such actions could result in a imprisonment between 3 and 10 years in Member States. Additionally, companies engaging in such criminal offences would face fines equal to at least 5% of their global turnover or an amount equivalent to €24 or €40 million. In comparison to the 2008 directive, it raises the number of environmental crimes from 8 to 20 and establishes minimum requirements, allowing Member States to be more stringent.

Furthermore, the ECD elaborates under which category the commitment of serious environmental crimes would fall. That is within the term ‘aggravated offence’ that would lead to more severe sanctions. Furthermore, national legislators are to contemplate the inclusion of aggravating factors and supplementary sanctions and measures (in addition to monetary penalties) to enable a customized response to individual offences. Consequently, persons who cooperate with the enforcement authorities in identifying the offenders of such serious environmental crimes will benefit from the supporting measures in such criminal proceedings.

The identification of such crimes, the enforcement of criminal law, and the punishment of the offenders in environmental crimes would require the work of criminal law enforcement agencies, prosecutors, and courts. This would presuppose a strong criminal law response that would lead to effective criminal law enforcement. Special training, the sufficiency of resources, and the efficiency of criminal law tools will be developed for the criminal law professionals to gain the needed qualifications and skills when combating environmental crimes. Considering the global nature and the cross-border element of environmental issues the new directive requires cooperation and coordination between the Member States.

In regards to this, the Commissioner of Justice Didier Reynders shared her hopes regarding the new directive on the 16th of November 2023 saying that:

‘This political agreement between the European Parliament and the Council is a major step forward in combatting environmental crime, a growing concern. This shows that the EU takes decisive action against environmental damage: the new rules set EU-wide standards to ensure environmental protection while providing for effective and dissuasive sanctions for offenders.’ The Commissioner for Environment, Oceans and Fisheries, Virginijus Sinkevičius, added that ‘Environmental crime causes devastating damage to our environment, harms our health as well as our economy. For too long criminals have profited from weak sanctions and lack of enforcement. With this strengthened law the EU steps up its action. It will better ensure that the most severe breaches of environmental rules are considered as crimes, that enforcers are more effective on the ground, and that environmental defenders are more protected and acknowledged.’

Moreover, the European Crime Directive criminalises the so-called ‘ecocide’, according to those who want to make it the fifth international crime prosecuted by the International Criminal Court. The directive refers to ‘cases comparable to ecocide’ in its preamble, but does not use the word in the directive explicitly. Ecocide is defined as ‘unlawful or wanton acts committed knowing that those acts have a substantial likelihood of causing severe and either long-term or widespread damage to the environment.’ The term was developed in 2021 by twelve international solicitors and made public by Stop Ecocide International. Thus, the European Parliament suggested enshrining the term in European law last year.

In conclusion, the European Crime Directive showcases the new priorities of the Union revolving around the growing environmental problems. To what extent will the new European Crime Directive be implemented by the Member States and what effect it is going to exert on the ongoing environmental crisis remains to be seen.

Europe’s Carbon Curtain

By Felix Kraft, 5 minutes. Global warming forces Europe to rethink its industrial production and sets national decision-makers before a legislative paradox. Meanwhile, Brussels has come up with a controversial solution that has the potential to either harmonise or rip apart the world’s entire supply chain network.

By Terk Felix Kraft, 5 minutes

Global warming forces Europe to rethink its industrial production and sets national decision-makers before a legislative paradox. Meanwhile, Brussels has come up with a controversial solution that has the potential to either harmonise or rip apart the world’s entire supply chain network.

In order to tackle climate change and species extinction, the European Green Deal prescribes to the European Union (EU), its countries, population, and decision-makers, a number of environmental targets to meet. One of these targets is climate neutrality by 2050 and meeting that aim is going to have an enormous impact on just about any aspect of our economy. In other words: Our elected officials will have to guide sectors 1 and 2 of our economy (agriculture and industry) towards largely climate-neutral means of production. However, once regulators start toughening environmental standards for goods produced in their country, they run into a paradox.

Backfiring Legislation

Let’s play a game: Imagine you’re a lawmaker and your aim is to raise environmental production standards, for example regarding CO2 pollution. You might do so by directly regulating business or through an Emissions Trading System (ETS), bringing to market a limited number of certificates that allow their owner to pollute. Whatever your precise formula, it inevitably increases production costs and disadvantages your country’s companies amongst their competitors from across the globe.

But is that bad, if it helps the environment?, you may ask. If only it did! By raising production costs, you have just incentivized firms from your country to move production abroad to places that might have even fewer and lower emission standards than those you had in the first place. Since all of us live on the same planet under the same atmosphere breathing the same air, you have effectively worsened the environmental situation for your constituents.

In addition, you’ve just wrecked a whole industrial sector, eliminated a range of specialised jobs, weakened your country’s position in global supply chains, undermined its Strategic Autonomy, and quite possibly shifted its trade balance. You’re essentially living an elected official’s perfect nightmare, one that is so prominent it got its own official title: Carbon Leakage.

Europe’s Patch on the Carbon Leak

Solving the paradox of practically increasing carbon emissions by toughening emissions standards might be one of the biggest riddles of our time - and the EU has taken it on to solve it! Just recently, on May 10th this year, the European Commission, Parliament, and Council signed the corresponding regulation, establishing a legislative monstrosity under its rather catchy name Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism or, in short, CBAM.

The EU’s CBAM designates a price to the carbon emitted during the production of carbon-intensive goods (aluminium, cement, fertiliser, electricity, hydrogen, iron and steel) outside the EU, upon entering its Single Market. As the EU itself raises its own climate ambitions, this protectionist measure is deemed necessary in order to prevent Carbon Leakage. The measure objectives are twofold: For one, it aims at protecting domestic production as it decarbonises.

Secondly, and this may be of even greater significance, it incentivizes producers abroad to adopt European environmental production standards in order not to have their products be slashed with what is effectively a carbon toll upon entering Europe’s rich, about 450 million-strong consumer market. Starting from October 1st, 2023, the gradual introduction of the CBAM shall take place in sync with phasing out the allocation of free allowances under the EU’s ETS.

Once fully implemented, CBAM will equalise the carbon price of imports with that of domestically produced goods of the same category. And whereas the EU claims its CBAM to be compatible with the rules of the World Trade Organisation (WTO), the exact set of rules and requirements for the reporting of emissions under CBAM shall be specified further within an implementing act. The WTO’s final verdict upon the EU’s CBAM, thus, is yet to come.

Ursula’s Climate Club

But the venture’s ultimate aim is not merely climate-neutral production in Europe, far from it. Utilising its sizable consumer market as leverage, the EU aims to convince producers (and, by extent, their legislators) outside the bloc of its high environmental production standards. In this way, the EU’s plans foresee consolidating the world’s major developed economies to form a kind of carbon free-trade area, a Climate Club. However, whereas countries like Canada and the United Kingdom have signalled interest, Washington, usually setting the tone on free trade, does not yet seem convinced.

At a later point, emerging economies such as Turkey and trade blocs such as MERCOSUR are supposed to find access to that same free-trade area - by climate-neutralising their agricultural and industrial production. The EU hopes its legislative endeavour will eventually cause a spill-over effect that reaches every corner of the globe, sets new climate-friendly production standards and, notably, establishes the EU as a global regulatory power in economic affairs. Ambitious? Certainly. Megalomaniac? Maybe.

Like the Sword of Damocles, the WTO’s final judgement on CBAM looms over the heads of busy Eurocrats elaborating product emissions tables. Meanwhile, Germany’s chancellor Olaf Scholz appears unimpressed. While refraining from elucidating the CBAM’s technicalities on camera, Scholz joyfully propagates the EU’s vision of a Climate Club to any global leader sparing an ear.

Legislative Gravity

But is this strong enough of an effort, grand enough of a pitch, to save the planet? Some MEPs, especially of the Greens/EFA Group, are not yet convinced. According to Rasmus Andresen, a German MEP for the Green Party, CBAM is going to contribute its part to global emissions reduction. He questions, however, whether CBAM “will be able to promote the establishment of a Climate Club in the sense of the Commission's legislative proposal within the required timeframe.” In other words: The tabled legislative act might lack the gravity to have a timely impact. Concretely, the MEP laments for the organic chemicals and plastics industries not being covered by CBAM as well as the time scope of the scheme’s time launch, which he describes as “very hesitant” and “a giant fly in the ointment”.

At the same time, Andresen considers it a success that, from 2030, all industrial products for which there is imminent Carbon Leakage risk (i.e. which can relatively easily relocate their production site) shall automatically become subject to CBAM. In this way, the scheme may - if belated - sharpen its accuracy.

Résumé

In the past, the EU has repeatedly proven its actorness in regulatory politics. Taking on major digital players in fields such as privacy and competition, it has been described as somewhat of a Regulatory Superpower. Publishing its legal text in a range of languages, Brussels is well aware of the spill-over effects its legislation has on states that might struggle to affirm the rule of law against foreign or corporate interests. Only time will tell, whether the EU will manage to transfer its regulatory abilities onto other, even more competitive policy fields or whether its ambitions end up hemmed in by more powerful global players.

To learn more about the topic, take a look at the EU’s climate ambitions:

European Green Deal:

https://www.commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en

https://ecamaastricht.org/blueandyellow-knowyourunion/europeangreendeal

European CBAM:

https://www.taxation-customs.ec.europa.eu/carbon-border-adjustment-mechanism_en

European ETS:

www.climate.ec.europa.eu/eu-action/eu-emissions-trading-system-eu-ets_en

Did You Know That a Water Agenda for The Mediterranean Exist?Here Is Why We Should Care About It

By Ilaria Settembrini, 9 minutes. I bet you did not know it. Fair enough. Still, the warming of the Mediterranean Sea is one of the fastest in the world and requires fruitful engagement by the EU. As an essential and historically contentious resource, water can offer Brussels new pathways for intergovernmental cooperation with the southern shores.

Source: UfM official website

By Ilaria Settembrini, 9 minutes

I bet you did not know it. Fair enough. Still, the warming of the Mediterranean Sea is one of the fastest in the world and requires fruitful engagement by the EU. As an essential and historically contentious resource, water can offer Brussels new pathways for intergovernmental cooperation with the southern shores.

We came a long way together…

2023 will mark 15 years since the establishment of a clear commitment of the EU towards ensuring water access in the Mediterranean region through a Water Agenda of the Mediterranean. The drafting of a water agenda was envisioned in December 2008 when, at the UfM Ministerial Conference on Water held in Jordan, the Euro-Mediterranean ministers promoted the establishment of a Water Expert Group (WEG). This group was set to provide a space in which states could gather information to develop shared goals for the future Agenda. Finally, it was in 2017 that the Malta Declaration mandated the finalization of the Agenda’s financial plan.