Press Freedom in Italy – A Human Right in Decline?

By: Lavinia Tacke

Reading time: 4:40 minutes

In January a European spyware scandal flooded the international media. The phones of “around 90 activists and journalists across Europe” were spied on with the use of the software of the Israeli company Paragon Solutions. According to the European Correspondent, the software can “read messages, record calls, track location and exfiltrate data from mobile devices”.

Seven of the 90 people affected were using Italian phone numbers, among them was Luca Casarini, founder of the NGO Mediterranea, which focuses on rescuing migrants in the Mediterranean Sea. Casarini is a vocal critic of Prime Minister Meloni’s policies.

It is unclear whether – or to what extent – the Italian government under Meloni is linked to the surveillance. However, as The European Correspondent reported, the government has admitted to maintaining a “business relationship with Paragon”

This scandal raises serious questions about the state of press freedom in the EU – particularly in Italy. In its 2024 report on press freedom, the NGO Reporters Without Borders described the situation in Italy as problematic, noting that “press freedom in Italy continues to be threatened by mafia organizations” and other extremist groups.

Furthermore, the NGO states that SLAPP procedures sometimes limit press freedom. SLAPP procedures, also called strategic lawsuits against public participation, are lawsuits that are launched to silence or intimidate journalists or and dissenting voices. Most often, SLAPP procedures are initiated by high officials or businesses.

According to the European Centre for Press & Media Freedom, SLAPP procedures have become a common tactic used against critical reporters, especially those reporting about “public figures and famous entrepreneurs”. Such lawsuits rarely succeed in court. They are employed in order to intimidate critics and discourage others from speaking out.

In addition to the widespread use of SLAPP procedures in Italy, the enactment of the Legge Bavaglio (“gag law”) in December 2023 has sparked further concerns over press freedom. Critics argue that the law significantly undermines journalistic transparency and the public’s right to information. The so-called gag law prohibits journalists from publishing juridical documents, such as pre-trial detention orders, before the end of the legal process. This controversial legislation has drawn strong criticism, including from members of the European Parliament who stated in a parliamentary question that “the gag law constitutes an absurd form of censorship and represents a lack of transparency in the work of the judicial bodies”.

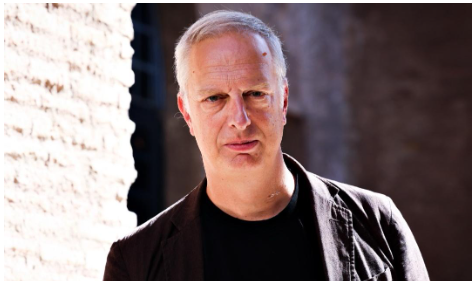

An article published by the Reuters Institute and the University of Oxford highlighted two specific instances of political interference in the Italian media sphere in 2024. When Antonio Scurati, a famous Italian writer who is known for writing a documentary novel about Mussolini and Italian fascism, was supposed to hold a TV monologue on an Italian public broadcaster in the context of Italy’s Liberation Day on 25 April 2024 it was cancelled last minute. The broadcaster declared it an “economic disagreement”, but the exact reasons for the cancellation remain unclear.

It later emerged that Scurati’s planned monologue harshly criticized Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni and her party, particularly by addressing the party’s neo-fascist roots. Despite the broadcaster denying any accusations of censorship and Meloni posting Scurati’s monologue on her official Facebook profile, the incident intensified concerns about the state of press freedom in Italy.

The Italian writer Antonio Scurati; picture source: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/apr/21/italy-antonio-scurati-rai-broadcaster-antifascist-monologue-cancellation

All these incidents have contributed to rising concerns about the status of press freedom in Italy. In its 2024 report, Reporters Without Borders ranked Italy 46th out of 180 countries, a noticeable decline in comparison to the previous report from 2023, where Italy was ranked 41st.

At the European level, Free Media was recently discussed in the context of enacting new EU rules against the SLAPP procedures and the European Media Freedom Act. In May 2024, the rules tackling strategic lawsuits against public participation entered into force, creating a system that is supposed to combat the use of SLAPPs against journalists. Additionally, the European Media Freedom Act set new rules aimed at protecting media independence and pluralism, which will be fully applied as of 8 August 2025. Part of the Act is measures to protect journalistic work from the use of spyware and to ensure media independence of public service media.