The crisis of incumbency - Part 2

By Ben Rosenbaum, Reading time: 3 minutes, 30 seconds

Why have so many governments struggled in recent elections, and why are populists’ extreme messages so successful? Problems with communication and narratives might be part of the answer.

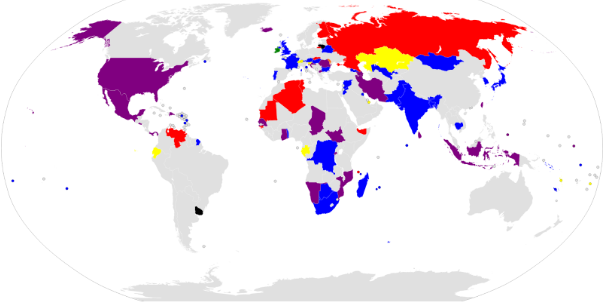

Elections in 2024: Executive (Red), Legislative (Blue), Executive and Legislative (Purple), Referendum (Yellow), Executive and Referendum (Orange), Legislative and Referendum (Green), Executive, Legislative and Referendum (Black), Constitutional Assembly (Pink)

Source: Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:2024_national_elections.svg#

In Part 1 of this series on the crisis of incumbency, I examined some of the reasons for the recent widespread rejections of governments in office, with many being voted out of office or losing majorities in elections. These losses have been attributed to the time of “polycrisis” in recent years, with natural disasters resulting from climate change, wars in Ukraine, the Middle East and Sudan as well as economic stagnation and uncertainty in many European countries. These interconnected issues have contributed to voters losing confidence in their national governments. According to the OECD, this was especially the case for people who felt “a lack of political voice and those with a sense of financial insecurity”. Such misgivings about the current political system and the governments embodying it are instrumentalized by populist and extremist forces. Parties like the AfD in Germany, the Rassemblement National in France and many others across Europe and beyond have benefited enormously from blaming current crises on political elites, immigrants, or both, and have thus channeled the dissatisfaction and anger of many into the direction of the incumbent government or the entire political system.

The benefits derived from this rhetoric are made clear by election results and current polling, with the AfD in Germany currently projected to come in second after the centre-right Christian Democratic Union in next February’s federal election. The CDU, too, is profiting to an extent from anti-incumbency sentiment, as popular opinion turned against the ruling Social Democrats, Greens and Liberal Democrats. But inside the CDU, another aspect of the crisis of incumbency at work can be observed: how to deal with the discontent of voters without further damaging the democratic system. A minority in the CDU is openly calling for a coalition with the AfD, while the party leadership has openly rejected the compromise. In its policies and appeals to voters, the CDU is walking a thin rope: pointing out the failures of the current government but without playing into the AfD’s hands. While decidedly more right-wing under Friedrich Merz than under more centrist Angela Merkel, the CDU is under pressure from both the right and the centre-left. The AfD is hoping for a coalition partner, while the centre-left and left parties criticise any indication that the CDU may follow the AfD’s populist rhetoric.

This small case study demonstrates the difficulty for the established political parties: showing voters that their discontent is registered and taken seriously, while also avoiding resorting to the same anti-establishment language that the populists are using. In this context, the right type of communication is vital, and politicians have often been criticised for not striking the right tone when talking to voters and arguing against populist policies. This was the case for the Democrats in the US, for example, and has repeatedly appeared in the case of the AfD. Trump‘s recent election win was explained partly through his blend of traditional and modern media, as well as sticking to his core message and attacking Kamala Harris on the record of the Biden administration.

Of course, the right communication is just one part of an election strategy, and just one part of the voters‘ decision-making processes. But it has been pointed out that the populists‘ simplified messages and narratives are effective in creating an emotional connection with dissatisfied voters. To counter these populist and often extremist narratives, analysts have suggested that democratic politicians need to find their own, positive narratives for their policies and communicate more effectively about how to deliver these policy promises. Additional points like more coherent long-term visions and strategies on issues like climate change, digitalisation and economic growth have also been raised in this context.

However, these suggestions are just a starting point. The crisis of incumbency is a complex phenomenon, with no singular reason and a different degree of gravity depending on country and circumstances. Nonetheless, it should give politicians food for thought on how to improve their policies, communication and approach to voters in order to sustain stable democratic governance.