THE EXCESSIVE FLEXIBILITY OF THE WORKING TIME DIRECTIVE AND ITS INADEQUACY IN PROTECTING WORKERS AFTER THE GREEK REFORM

By Aurora Dagnino, reading time: 5 minutes and 45 seconds

Greece's parliament approved a few weeks ago a contested labour bill that would allow 13-hour workdays, despite strong opposition from labour unions, opposition lawmakers, and civil society groups, all of whom argued that the measure undermines worker protections. Two nationwide strikes were held in the space of two weeks from early October, paralyzing the country. In both Athens and Thessaloniki, transportation networks were shut down, while hospital staff, teachers and other civil servants stopped working.

Workers’ protest, BBC: Greece passes labour law allowing 13-hour workdays in some cases

Under the new law, workers in certain sectors, such as manufacturing, retail, agriculture, and hospitality, could work for up to 13 hours per day, but only for a limited number of days each year: 37. Employees will remain bound by an overall cap of 48 working hours per week, calculated on a four-month average, with the general 40-hour workweek continuing as the standard. The total annual overtime permitted continues to be 150 hours, and workers performing overtime will receive an additional 40 percent on top of their regular wages. The government has highlighted that participation in the 13-hour schedule will be strictly voluntary and subject to the employee’s consent.

This new law comes with no surprise, and it seems to reflect a trend that goes in the opposite direction with the rest of Europe, where an increasing number of countries are reducing the working week. In 2024, Greece introduced a six-day working week for certain industries to try to boost economic growth.

The legislation, which came into effect at the start of July, allows employees to work up to 48 hours in a week as opposed to 40. It must be said that it only applies to businesses which operate on a 24-hour basis and is optional for workers, who get paid an extra 40% for the overtime they do.

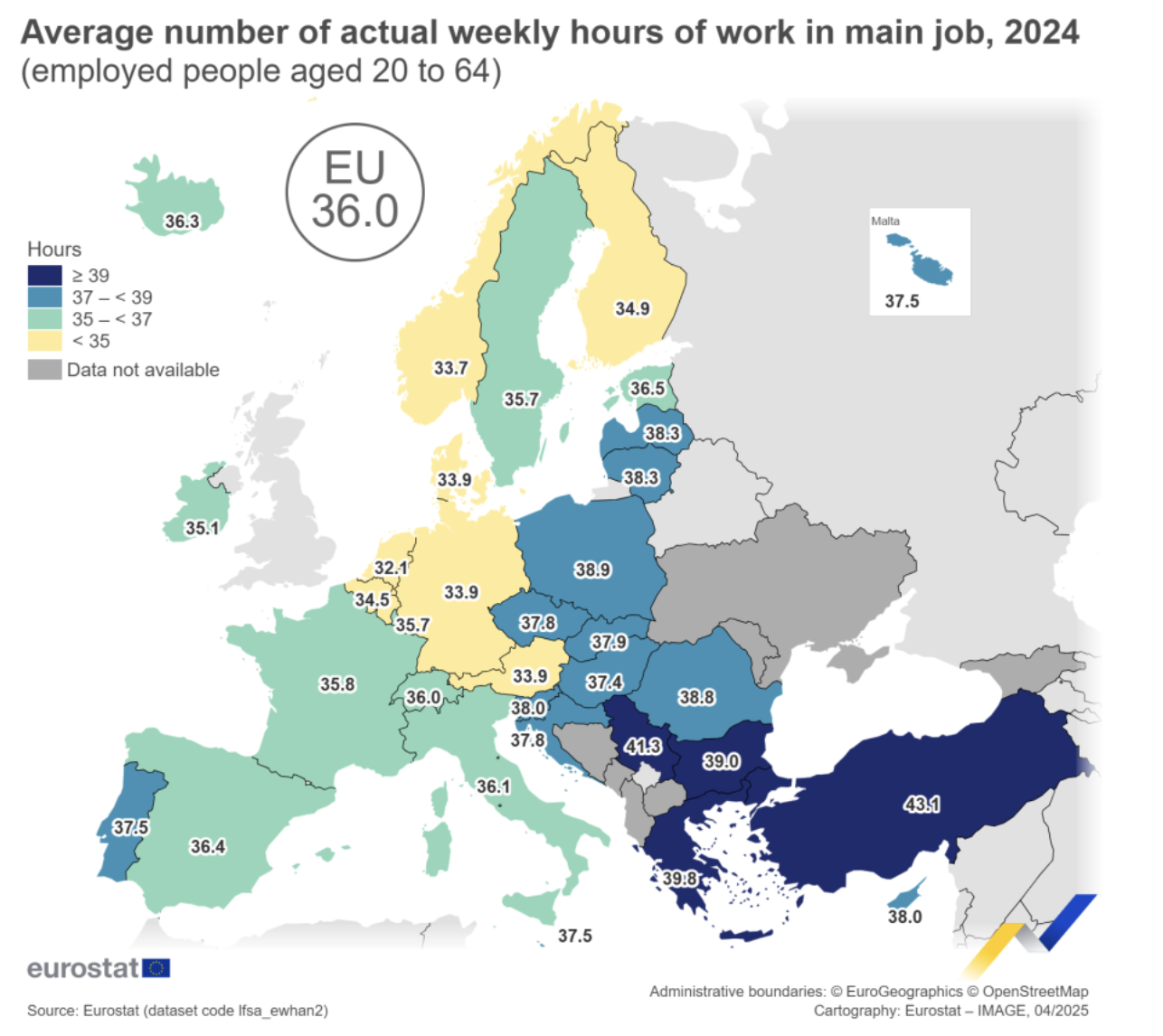

In 2024, the average working week at EU level lasted 36.0 hours. This varied across the EU, from 32.1 actual hours of work in the Netherlands to 39.8 in Greece, showing the Greek contradictory trend.

But what does EU law say about this? Is there any limit on the maximum duration of a working day?

The relevant piece of legislation here is the Directive 2003/88, hereinafter called “working time directive”. The aforementioned does not explicitly establish how long a working day could be, but it could be derived implicitly. Let’s take a look at the relevant articles:

Article 3 defines daily rest and establishes that every worker is entitled to a minimum daily rest period of 11 consecutive hours per 24-hour period.

Article 4 disciplines breaks, entitling workers to a rest break after 6 hours of work.

Article 5 regulates the weekly rest period, granting workers a minimum uninterrupted rest period of 24 hours plus the 11 hours' daily rest referred to in Article 3.

Article 6 is also relevant, which limits average weekly working time (including overtime) to 48 hours. This limit is calculated over a reference period (usually 4 months)

From this we can determine that the maximum duration of a working day is 13 hours (24h - 11h rest); therefore, legally speaking, the Greek government has not breached any EU law.

Moreover, under Article 17, derogations from the daily rest period (Article 3) and breaks (Article 4) can be implemented in activities involving the need for continuity of service or production. Thus, by applying the 13 hours only to certain sectors, Greece acted fully within the boundaries of the working time Directive.

But is a 13 hour day really doable? Where is the respect for social and private life? Is it beneficial for the productivity of the worker? It goes without saying that working for 13 hours is hardly tenable, both from a physical and psychological point of view.

Furthermore, the argument that there is no obligation on the worker and that participation is voluntary is not realistically applicable in the labour scenario, where we have an asymmetry of power between the employee and the employer.

As if this wasn’t enough, Article 22 of the Directive, allows Member States not to apply the standard maximum limit on weekly working time. Through this opt-out mechanism, EU Member States can require workers to agree to work more than 48 hours over a seven-day period.

It is for these reasons that the Directive should explicitly put a ceiling on the duration of the working day, avoiding granting so much flexibility to employers, both in terms of the duration of the working day but also the duration of the breaks.

Another point of criticism of the Directive is that it does not specify whether the working time limit should apply per worker (covering all jobs held by an individual) or per contract (applying limits separately to each job). If the primary goal is protecting the health and safety of workers, it should apply per worker; however, many Member States applied it per contract.

The Directive has been additionally attacked because it does not adequately define how on-call duty should be treated, meaning periods when a worker is required to be available for work, but not necessarily working the entire time. An example is a doctor who must stay at the hospital overnight in case of emergencies or a firefighter who must be ready to respond immediately, even if resting at the station.

The issue here are the vague definitions in article 2 of "working time" and "rest period": working time is defined as "any period during which the worker is working, at the employer's disposal, and carrying out his activity or duties"; while rest period is defined simply as "any period which is not working time".

Ergo, the Directive failed to address the time spent on-call, which often involves long periods of inactivity combined with the requirement to be available. While the legislation is uncertain on this merits, the CJEU has already clarified the point, but legislative attempts to amend the Directive to counter these rulings have failed.

In the SIMAP Case (C‑303/98, 2000) the CJEU consistently ruled that inactive time spent on-call at the workplace must be counted as working time in its entirety. Despite the clear CJEU ruling, compliance and interpretation across Member States remain problematic: in some Member States, only active on-call duty at the workplace is counted as working time (e.g., Poland and Slovenia). Similarly, in Slovakia, on-call duty at the workplace does not fully count as working time for certain groups.

More than 20 years after its entry into force, the Directive is clearly unfitted to regulate nowadays working dynamics and suffers from being too vague and flexible. It leaves important, basic issues unaddressed, which has led to persistent legal confusion and fragmented practice among Member States. Moreover, its full application can be avoided through opt-outs and derogations, putting at risk the health and safety of workers, which should be the primary aim of the Directive, but which in practice is often not achieved.