How does the European Union protect human rights?

By Lucrezia Nicosia, 7 minutes. This article aims at explaining how the European Union guarantees the protection of human rights of its citizens/residents; this will be done by explaining the scope and content of the EU Charter, its similarities with the ECHR, and the main bodies involved in the framework.

Source: Debating Europe

by Lucrezia Nicosia, 7 minutes

The protection of human rights represents one of the main values of the European Union, as laid down in the Treaty on the European Union (TEU) and in the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU).

The main provision outlining the concept is Article 2 TEU, which states:

The Union is founded on the values of respect for human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality, the rule of law and respect for human rights.

Furthermore, according to the wording of Article 3(5) TEU:

[The EU] shall contribute to peace, security, the sustainable development of the Earth, solidarity and mutual respect among peoples, free and fair trade, eradication of poverty and the protection of human rights, in particular the rights of the child, as well as to the strict observance and the development of international law, including respect for the principles of the United Nations Charter.

For what concerns the area of common foreign and security policy, and according to Article 21 TEU (later confirmed in Article 205 TFEU):

The Union's action on the international scene shall be guided by the principles which have inspired its own creation, development and enlargement, and which it seeks to advance in the wider world: democracy, the rule of law, the universality and indivisibility of human rights and fundamental freedoms, respect for human dignity, the principles of equality and solidarity, and respect for the principles of the United Nations Charter and international law.

Two specific legal instruments play an important role when discussing the topic of human rights protection within the European Union: the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) and the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (EU Charter). While being closely connected to each other, they have been issued by two different entities: the Council of Europe and the European Union respectively.

This article aims at explaining how the European Union guarantees the protection of the human rights of its citizens/residents. This will be done by explaining the scope and content of the EU Charter, its similarities with the ECHR, and the main bodies involved.

What is the European Convention on Human Rights?

Source: Council of Europe

The ECHR is a regional instrument drafted on the 4th November 1950 and to which all Contracting Parties that belong to the Council of Europe (CoE) are parties. The CoE is an international organization primarily concerned with developing and spreading awareness on human rights around Europe and which must not be confused with the European Council or the Council of the European Union. Indeed, while these institutions are part of the EU, the CoE is an independent organization that comprises 47 States, including all 27 EU Member States.

The ECHR forms part of the general principles common to all the Member States now in Article 6(3) TEU:

Fundamental rights, as guaranteed by the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms [ECHR] and as they result from the constitutional traditions common to the Member States, shall constitute general principles of the Union's law.

This way, within the framework of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), an international court of the CoE which interprets and applies the provisions of the ECHR, the EU Member States hold a so-called “presumption of equivalent protection”. The latter was elaborated in the Bosphorus case and it has been used by the ECtHR in order to balance the Contracting States’ obligations under the ECHR and EU law: when a case against an EU Member State is brought before the ECtHR, and the alleged violation concerns the application of EU law, the Court will presume that there has been equivalent protection of the ECHR. However, such presumption may be rebutted if there are signs of manifest deficiency.

What is the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union?

The Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union was initially proposed by the European Council in 1999 and it was solemnly proclaimed on 7 December 2000 by the European Parliament, the Council of Ministers and the European Commission. Nevertheless, it was initially not legally binding, but taken into consideration as soft law. The EU Charter gained full legal effects on EU Member States when the Treaty of Lisbon entered into force in December 2009. Currently, the EU Charter is considered, together with the TEU and the TFEU, as part of EU primary law.

The EU Charter is divided into six chapters, which divide the different categories of rights:

Dignity (e.g. human dignity, right to life, right to integrity of the person, prohibition of torture and inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment);

Freedoms (e.g. right to liberty and security, respect for private life and family life, freedom of thought, conscience and religion);

Equality (e.g. equality before the law, non-discrimination)

Solidarity (e.g. workers’ right to information and consultation, fair and just working conditions)

Citizen’s rights (e.g. right to vote, right to good administration, right of access to documents held by any EU institutions)

Justice (e.g. right to an effective remedy and to a fair trial, presumption of innocence and right of defence)

As laid down in Article 51 EU Charter:

The provisions of this Charter are addressed to the institutions and bodies of the Union with due regard for the principle of subsidiarity and to the Member States only when they are implementing Union law.

Therefore, Member States are bound by EU human rights standards at the moment that they implement EU law, when national legislation falls into the scope of EU law, and when they derogate from fundamental freedoms.

Member States technically have the possibility to opt out from legislation or treaties of the European Union, meaning they do not have to participate in certain policy areas. This seems to have happened to the United Kingdom and Poland according to Protocol no. 30 EU Charter. However, this cannot be considered an actual opt-out, but better as a “clarification” since the Protocol cannot exempt the UK and Poland from human rights standards already recognized by EU case law and that belong to the general principles of law under Article 6(3) TEU. Indeed, EU Member States are always bound, when acting within the scope of EU law, by the human rights standards already recognized by EU case law and that belong to the general principles of law under Article 6(3) TEU.

To review the progress in implementing and respecting human rights standards, the European Commission draws up annual reports prepared in close collaboration with all institutions and relevant stakeholders on the application of the EU Charter by the Member States.

Furthermore, the EU Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) covers an important role in this field. On the one hand, it gives independent advice to EU institutions and the Member States on the rights set out in the Charter; on the other hand, it conducts legal and social research to better improve the level of protection of human rights in the EU and to align them to international standards.

What are the main differences between ECHR and EU Charter?

The ECHR was drafted by the Council of Europe, an international organization that includes 47 Contracting Parties. On the other hand, the EU Charter is an instrument of the European Union, applicable only to EU member states.

Contracting Parties to the ECHR are bound by it in all actions or omissions within their jurisdiction, while Member States are bound to the EU Charter only when acting within the scope of EU law.

The EU Charter enshrines some rights that are not guaranteed in the ECHR, as for example the right to asylum or the right to data protection. Although the latter is not expressly governed in the ECHR, there is a lot of ECtHR case-law on the matter on the basis of Article 8 ECHR.

Within the framework of the ECHR, there is a specific court that checks on the observance of the Convention. Indeed, individuals whose rights have been violated can take the case to the European Court of Human Rights. On the contrary, within the system of the EU Charter, there is no court to which individuals can apply directly. This can be done only indirectly through the work of the Court of Justice of the European Union.

That being said, the system of the European Union and of the Council of Europe are intertwined because the provisions laid down in the ECHR have been used as a basis for the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights. Furthermore, all 27 EU Member States are also members of the Council of Europe and therefore bound by its human rights standards.

The Multiannual Financial Framework - policy up close

By Erik Schmidt-Bergemann, 5 minutes. Every seven years the EU needs to pass a new budget. The last Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) was passed in 2020 and the new budget will run from 2021 till 2027. This article will explain what the budget entails and how the policy-making process works.

by Erik Schmidt-Bergemann, 5 minutes

Every seven years the member states of the European Union come together and decide on the new multiannual financial framework or the budget of the European Union (EU). The last budget ran out at the end of 2020, in the middle of the Covid-19 pandemic, and member states had to come together and negotiate the new framework for the 2021-2027 budget period. This article will cover the new budget in detail and will offer a short explanation of the budget in general.

What is the multiannual financial framework?

The so-called multiannual financial framework (or short MFF) has been used in the EU since 1988. The MFF usually runs for seven years (the required minimum is five years) and touches upon basically every aspect of the EU. For example, programs such as Erasmus or Horizon Europe are funded by the MFF. The MFF sets a yearly limit on commitments and payments that the EU can make. However, in the case of unforeseen circumstances, such as a sudden crisis, the EU has several financial instruments at its disposal to address these sufficiently.

But who makes the initial proposal of the budget and who are the key players in the decision-making process? The Commission starts the process of passing the budget by presenting an initial proposal. This initial proposal will then move on to the Council which may change the proposal by the Commission. Thus, the member states play a central role in the budget decision-making process and can influence the budget. After the Council is done with changing the proposal from the Commission, the budget moves on to the European Parliament. However, it cannot make any official changes to the proposal at this stage since it is not a co-legislator but rather is only asked for consent since the MFF is following the consent procedure. Thus, the Parliament needs to inofficially influence the budget while the EU member states are negotiating it in the Council. After the European Parliament has given its consent to the budget, the Council needs to adopt the budget through a unanimous vote. The legal basis for this is article 312 in the TFEU.

The new budget 2021-2027

Figure 1: European Commission The 2021-2027 MFF

In 2020 the member states had to pass the new budget for the period of 2021-2027. The new budget will encompass €1.211 trillion which are combined with €806.9 billion in the recovery package. The recovery package is what makes this MFF particularly interesting. Due to the unprecedented Covid-19 crisis and its impact on the European economy, the member states have decided to set up a recovery package to limit the negative effects of the Covid-19 crisis on European economies and help the states that have been hit the hardest by the pandemic. The influence of the pandemic on the MFF will be covered in detail below.

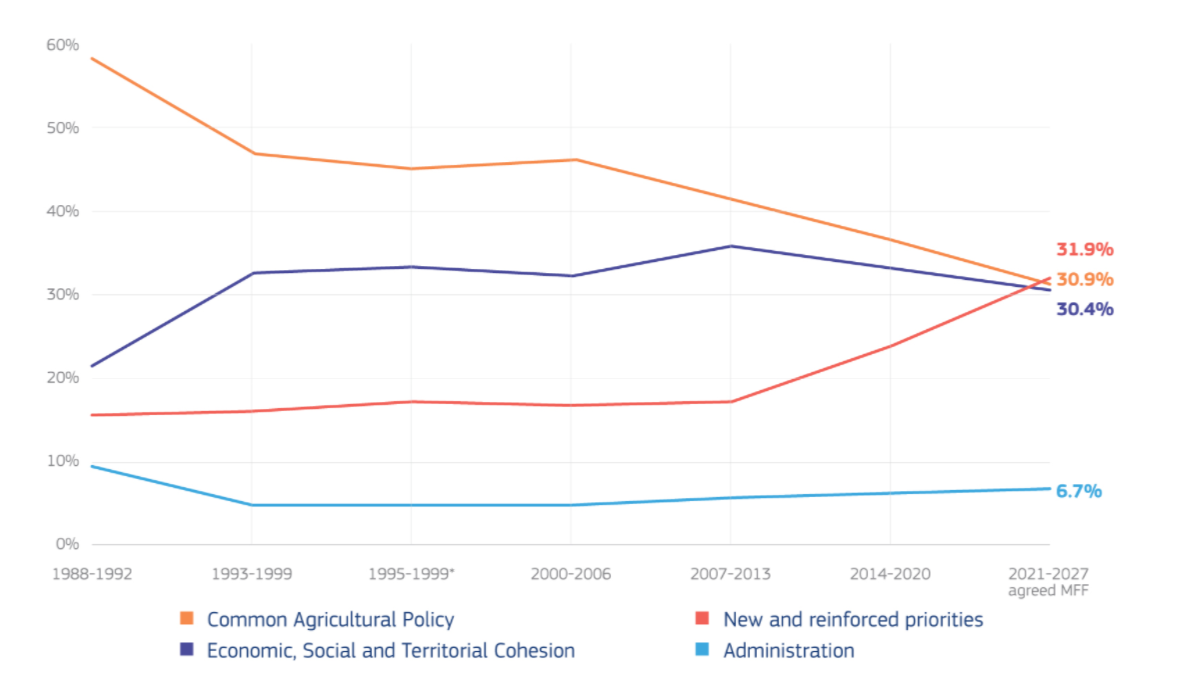

The MFF has seen some changes since the first budget was adopted in 1988. Whereas the first three decades had seen a focus on the Common Agricultural Policy and Cohesion Policy, the new budget will shift its focus to new priorities. These new priorities include investments into research and innovation, combating climate change, the transition to the new digital era and the recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic. This exemplifies the new focus on the budget and Figure 2 shows that these new priorities are receiving the largest share in the 2021-2027 MFF. If you want to dive into the details of the new MFF, this brochure by the EU is a good starting point.

Figure 2: European Commission

Another new addition to the 2021-2027 MFF is the so-called “conditionality regulation”. This new regulation has been introduced to address rule of law breaches by member states. An example of a rule of law breach would be if a certain member state does not implement rulings by the Court of Justice. However, this conditionality only applies if “a given member state threaten the EU financial interests” (Source: European Commission). Thus, rule of law breaches that do not threaten the EU’s financial interests are not affected by the new conditionality regulation.

Yet, if a member state should threaten the financial interests of the EU, the Commission is responsible for proposing appropriate measures to the Council to address the breaches by the member state in question. After the Commission has proposed measures to the Council, the Council will make a final decision on the proposal.

The Covid recovery package

Due to the Covid-19 crisis and its huge economic impact on the European economy, the EU has decided to include a recovery package in combination with the new MFF. The main aims of this recovery package are to limit the negative effects of the Covid-19 pandemic and to transform Europe into a digital and sustainable continent. The funds that are allocated under the Recovery and Resilience Facility are directly paid to the member states after the member states have submitted a Recovery and Resilience plan. These plans need to address several challenges including climate change and digitalisation. Once a member state has submitted its plan the Commission will assess it and the European Council will approve it. Once the plan has been approved by the European Council, the member state will receive its allocated funds.

As aforementioned, most of the funds will be used to increase Europe’s digital capabilities and to make European economies ‘green’ and sustainable. Figure 3 showcases several areas that will receive funding under the Recovery and Resilience Facility such as improving digitalisation in public administration or investing in renewable technologies such as solar energy.

Figure 3: European Commission