THE GREAT COHESION REWRITE: Reform or Regression? PART I

By: Olaia Mujika Anduiza Estimated reading time: 5 minutes

Image credits:Paulgrecaud

Lately, disputes over the next Multiannual Financial Framework (2028–2034) have been making headlines. This is no surprise: the MFF, as the EU’s long-term budget, is central to economic and financial planning and shapes a wide range of EU priorities. As a result, its drafting always involves significant disagreement and negotiation between institutions, political parties, and Member States.

What did come as a surprise this year was that the Commission’s proposal aims to deeply reshape core EU policies, including cohesion policy. In fact, in this policy area, the Commission is even going against the advice of its own key experts on reform options.

To better understand how cohesion policy works today and how the Commission proposes to change it, a concise two-part series on the topic will be published. The first article outlines the current architecture of cohesion policy, while the second will examine the Commission’s proposed reforms.

Let us begin with the first.

The basics about Cohesion Policy 2027-2034

When Jacques Delors launched his vision of the Single Market in 1985, he warned that its benefits would not be felt equally across Europe. Wealth, he foresaw, would cluster in urban centres while the peripheries risked being left behind.

This imbalance threatened Europe on two fronts: its competitiveness, wasted if confined to a few; and its unity, fractured by the political and social rifts of uneven prosperity. This would enventually result in a divided, and therefore diminished, Europe.

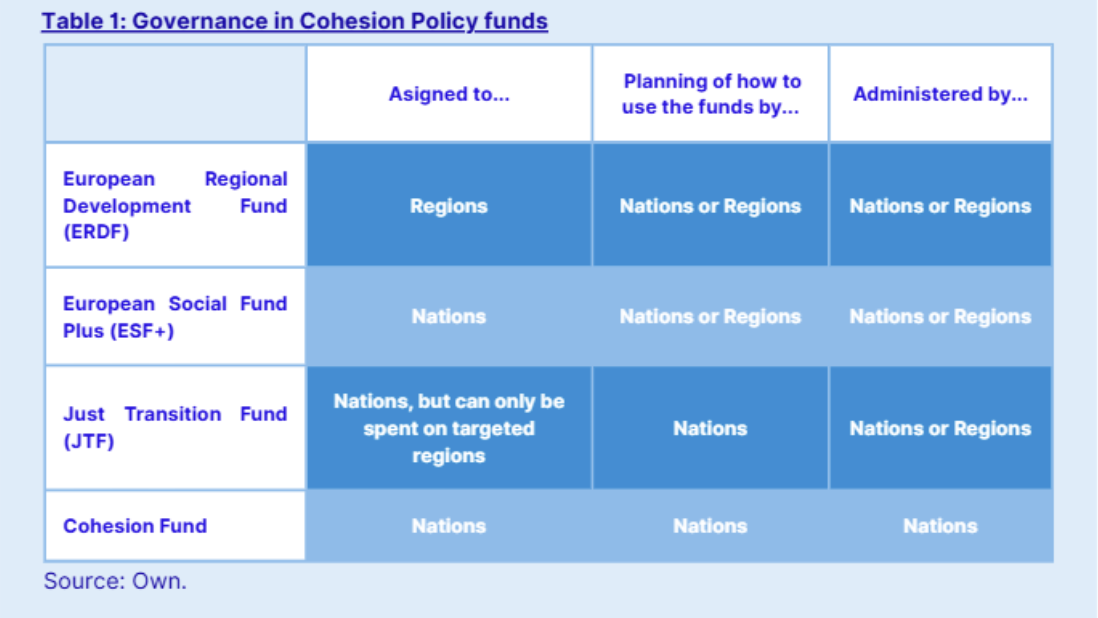

To prevent this, Cohesion Policy aims to correct structural imbalances created by the Single Market by redistributing growth opportunities across EU regions. In the 2021–2027 Multiannual Financial Framework, it receives €392 billion, excluding national co-financing. The money is divided into four funds with distinct goals and varying degrees of national and regional involvement.

Importantly, all funds are jointly managed by the European Commission and Member States or regions. The Commission sets the broad rules and priorities, while regions and Member States design their own programmes in consultation with local partners.

This bottom-up model helps identify where investment is most needed, and brings policymaking closer to citizens, which is relevant because Cohesion must adapt to the realities of each place. However, the system is complex, paperwork-heavy, and often slow to deliver results.

Diagnosing Cohesion Policy’s Weaknesses

However, persistent disparities, loss of identity, excessive complexity, and weak evaluation mechanisms have eroded Cohesion policy’s effectiveness. These issues are summarized below.

Money flows, but disparities hold:

Several regions in Southern Europe have received cohesion funds for decades, yet they still struggle to build lasting, self-sustaining growth. The result is a persistent gap between these regions and the EU’s more advanced areas.

Two main factors explain this: cohesion policy often misses its primary targets, and deep gaps remain in innovation and institutional strength. First, while cohesion policy may lift average incomes on paper, the gains often go to higher-income groups within poorer areas, widening local inequalities.

Secondly, the success of regional investment heavily depends on the quality of local institutional and macroeconomic conditions. Still, in the poorest regions, weak institutions and poor innovation ecosystems still hinder both fund absorption and sustained growth.

Cohesion’s loss of identity:

Cohesion policy was designed for a specific purpose: to distribute the benefits of EU integration and narrow economic gaps. However, it has increasingly become a catch-all agenda due to the overwhelming number of goals it now covers (green and digital transitions, youth unemployment etc.). This accumulation dilutes focus and makes overall progress appear limited.

Moreover, this long-term policy has repeatedly been adapted to enable rapid crisis responses, most recently in the EU’s reaction to the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act. While flexibility can be valuable, repeated use for crisis management undermines strategic consistency and blurs its developmental purpose.

Cohesion without coherence:

Over the years, cohesion policy has become increasingly complex even though recent reforms were meant to simplify it. One major reason is the growing fragmentation of funds.

Some programmes that once formed part of cohesion policy (like the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development) were moved under other frameworks, such as the Common Agricultural Policy. While they still aim to support development, they no longer follow cohesion’s guiding rules.

At the same time, the remaining funds, such as the ESF+, have been increasingly tied to broader EU agendas like the European Semester and the Social Pillar, drifting away from the policy’s original goal of reducing regional disparities.

Consequently, cohesion policy now lacks coherence and coordination, being turned into a fragmented system of overlapping rules, procedures, and priorities that obstruct effective planning and implementation.

Formalism over function:

The evaluation of Cohesion Policy has become a formalistic exercise and is largely ineffective in ensuring compliance with EU standards. For this reason, actors such as the Conference of Peripheral Maritime Regions (representing over 160 regions across Member States) have suggested to link the disbursement of funds to the achievement of specific milestones or reforms.

United in goals, separated in means

There is broad consensus that cohesion policy is in need of reform. The upcoming MFF 2028–2034 was the ideal opportunity to address the shortcomings outlined above and strengthen the policy’s effectiveness in building a more united and competitive Europe.

The details of the Commission’s proposal to reform will be explored in the second article of this series, but here is a preview: it neither tackles the policy’s core weaknesses nor reflects the interests of the regions and stakeholders who rely on it most.

Stay tuned for a closer look at what may reshape Europe’s cohesion landscape.