Security starts at the Rail Station - Interview on military mobility with Terk Felix Kraft Part I

By: Olaia Mujika Anduiza and Lavinia Tacke, Reading time: 8 Minutes

Source: unsplash

While Europe is discussing military issues mostly in terms of conscription and the reconfiguration of alliances, one topic that remains largely overlooked by the broader media is arguably more important than ever: the EU’s military mobility infrastructure. In recent years, the EU has faced a serious backdrop of capability gaps in its military mobility infrastructure. Some shortcomings have become so severe that countries are now considering reactivating long-unused and, in part, dysfunctional infrastructure. The scale and urgency of current demands, driven by support for Ukraine and the extension of NATO's border with Russia due to Finland's accession to the alliance, have exposed the limits of Europe’s existing capacity.

Let’s take a moment to look at military mobility and how it is being managed in the EU. To that end, this article is divided into two parts: the first offers a snapshot of the current state of military mobility, and the second examines the new package presented by the European Commission.

To shed light on this topic, Terk Felix Kraft, who until recently has been leading work on military mobility at the Association of European Railway Infrastructure Managers (EIM), shared his expertise with us. After completing his Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees in European Studies at Maastricht University, he started working for the EIM in February 2025.

The Association of European Railway Infrastructure Managers (short EIM) and its task

In Felix’s words, “EIM is one of about a dozen officially recognized interest-representing organizations in the railway sector [...] in Brussels”. The organization's members are “mostly public or quasi-public companies who manage railway infrastructure” in the EU countries.

The interviewee: Terk Felix Kraft

Source: pixabay

Edit: Lavinia Tacke

A united EU - not when it comes to the railway infrastructure

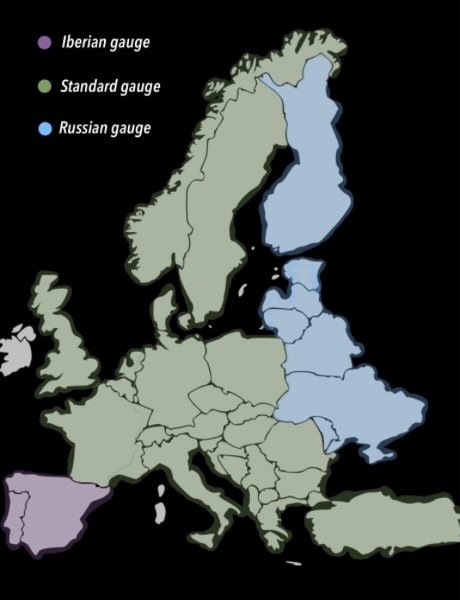

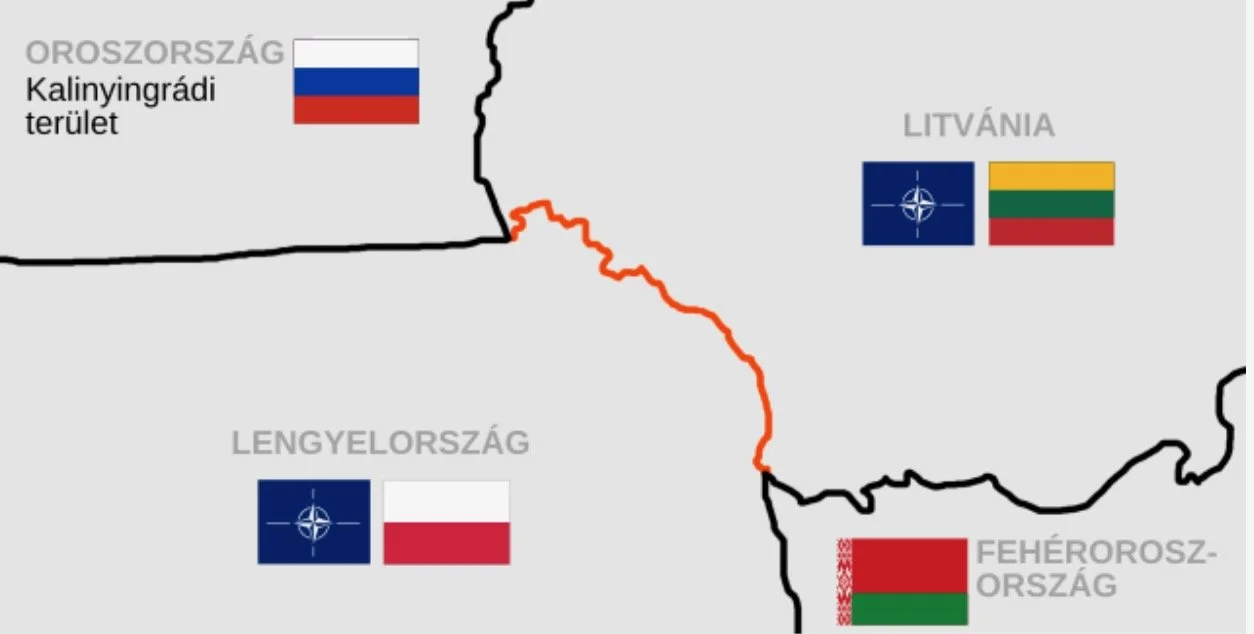

One of the most prominent issues in the EU’s military mobility stems from the many discrepancies between member states’ railway infrastructures. Track gauges and electrical systems differ from country to country, which means equipment cannot always be transported across borders without obstacles. Most central and western European countries use the European or standard gauge. Spain and Portugal use the Iberian gauge. The Baltic States, Finland, Moldova, and Ukraine, however, still use the Russian gauge for historical reasons. “They were part of the Tsarist Empire during the Industrial Revolution,” Felix explains. This fragmentation undermines Europe’s railway network, leaving the Finland and Baltic states somewhat isolated “within the NATO alliance and also within the EU”. Felix calls it a “logistical nightmare” and notes that the Rail Baltica and Rail Nordica projects aim to connect these countries to Poland and Sweden respectively by extending the European standard gauge to the region. “Right now, there is just one railway line between Poland and Lithuania, and it uses the Russian gauge”. As if this were not enough, Felix goes on to clarify that the Baltic region is particularly vulnerable. Poland and Lithuania share only a short common border, known as the Suwałki Gap or Suwałki Corridor, located between Belarus and the Russian exclave of Kaliningrad Oblast. The pressing question is: “How do we pump as much military capability as possible into the Baltic States before Russia closes the Suwałki Corridor […]?” Here, we are discussing not only military units but also medical supplies, such as blood and plasma containers.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

The red line represents the Suwałki Corridor

If you would like to know more about the geostrategic situation around the Suwałki Corridor, check out this article.

The problem with electricity

What also becomes clear in Felix’ explanations is that one of the EU’s key vulnerabilities is its ability to maintain military mobility during a major power outage, like the one that occurred in Portugal and Spain in 2025. One obvious solution would be to rely on diesel trains, yet Europe no longer has the industrial capacity to produce pure diesel rolling stock. Hybrid trains may offer a partial workaround, Felix noted, but this would likely entail a limited reduction in fossil fuel use. Electrification, while environmentally sound, is also fragile and creates resilience risks. This reinforces the need (at least in the short term) to fall back on older equipment, as already seen with some of the material sent to Ukraine.

Is the Commission paying enough attention to these gaps?

When we talked about the Commission’s work on the EU’s military mobility, it became clear that this cannot be answered with a simple yes or no. Felix states: “On the one hand, it is good that they prioritize.” The Commission sets up its priority list according to three parameters: “the budget, the time, and the military significance”.

Nevertheless, Felix criticizes that “the budget could always be bigger” and that the Commission’s prioritization is not always effective from a military perspective. Some of the projects on the priority list are located in Spain or Portugal. “It is always a given in the European Union that you have to find a certain proportionality amongst member states, but from a military point of view, that’s not smart”, Felix argues.

The EU moves towards a Military Schengen - but what does that actually mean?

“Military Schengen” is a term that one quickly comes across when researching the EU’s efforts on military mobility. The Commission itself describes its proposed military mobility package as a step towards a “military Schengen.” In essence, this means extending the Schengen rules to most military goods and personnel by removing trade and administrative barriers. Felix explains that “when the Schengen area was developed, they excluded military products because, technically speaking, if you are country A and you move into country B with arms, without diplomatic clearance in advance, then that is an act of war”. Therefore, diplomatic clearance is necessary. If implemented as it currently stands, the Commission's proposal would largely resolve the issue of lengthy diplomatic clearance processes. Felix is hopeful that the member states will “understand the urgency” and refrain from pointing at their national sovereignty in this matter. After this explanation, it is clear that a military Schengen is essential to the EU’s security.

The Ukraine war - a cause for the issues or simply a signalizer?

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 put the topic of military security back on the table, but Felix explains that it has mostly just “intensified the problem” of the EU’s military mobility. Nevertheless, the consequence of Finland and Sweden’s accession to NATO “has created new possibilities and new problems”.

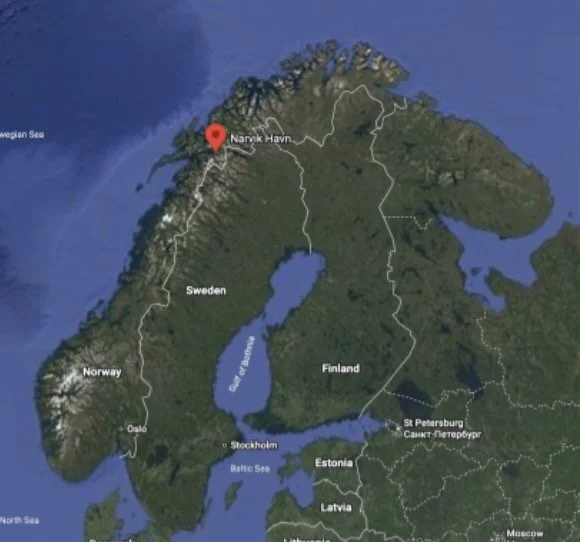

source: Google Maps

Location Port Narvik

The situation at the Norwegian port of Narvik is one example of the consequences of this NATO enlargement. Previously, Norway was mostly concerned with north-south traffic, but since Finland and Sweden joined the alliance, the east-west movements across the Scandinavian countries have become a central concern. As a result, the port of Narvik in northern Norway has gained new significance within NATO’s infrastructure network and therefore requires some upgrades to be able to handle the increased east-west traffic.

The interview with Terk Felix Kraft sheds light on some urgent issues the EU faces regarding its military mobility. To address them, the Commission put forward a Military Mobility Package consisting of a regulatory proposal and measures aimed at eliminating internal EU barriers to military mobility. The mission is clear: the EU wants to move closer to a “Military Schengen”. We did not miss the opportunity to ask Terk Felix Kraft in detail about what this package entails and what obstacles can be expected. To find out more about this, stay tuned for part two!