The Crisis Unfolding in European Prisons

Written by: S.J.C Gunning, Reading time: 5 min

Image Credit: VRT

Mattresses in bathrooms, prisoners “having to eat their meals standing up or sitting on the floor, sometimes with no access to basic amenities like pillows or clothes-washing facilities,” and even the rape and murder of prisoners by their own bunkmates in overcrowded prison cells are not the anecdotes of a survivor of the gulags but rather features of everyday life for prisoners in more than half of the European Union’s member states. According to the most recent Eurostat survey, taken in 2023, 14 countries had some extra capacity while 13 countries had none at all and had to overcrowd existing cells. However, more recent data from the World Prison Brief adds Portugal and Hungary to the growing number of EU member states with prison occupancy rates above 100%.

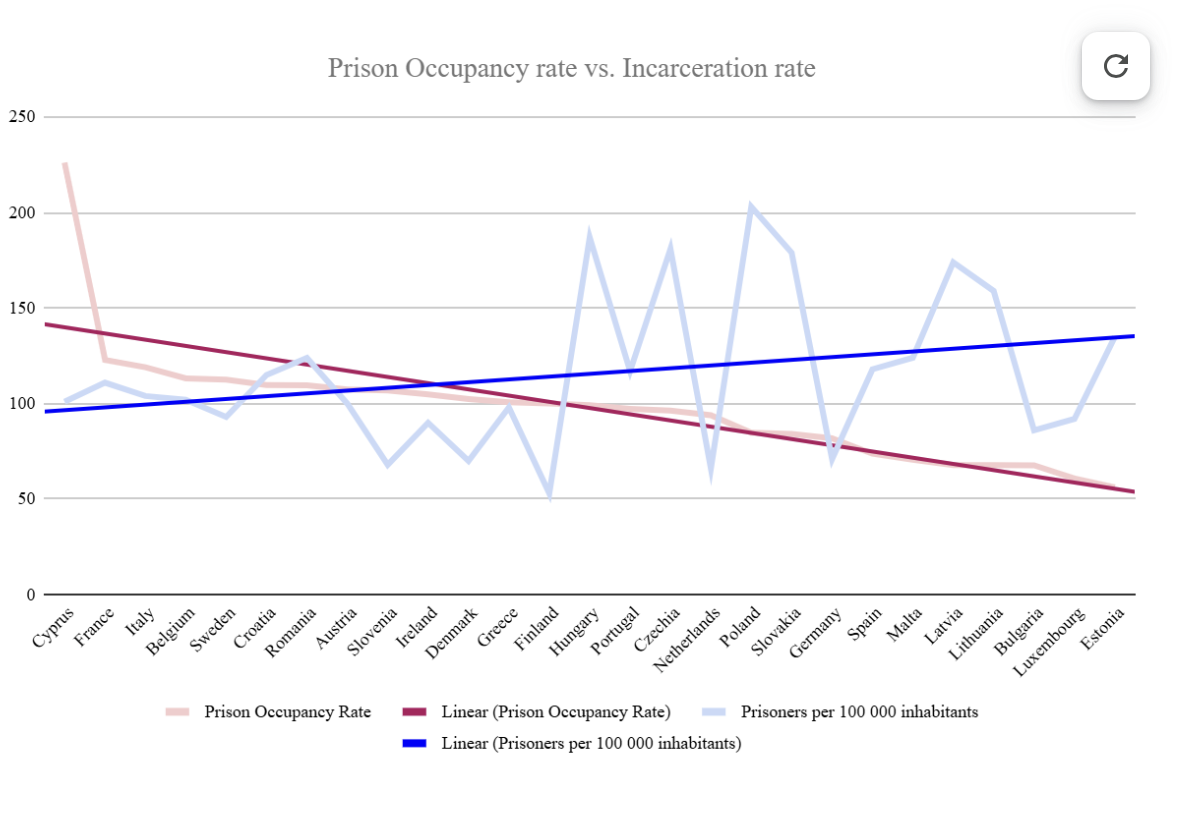

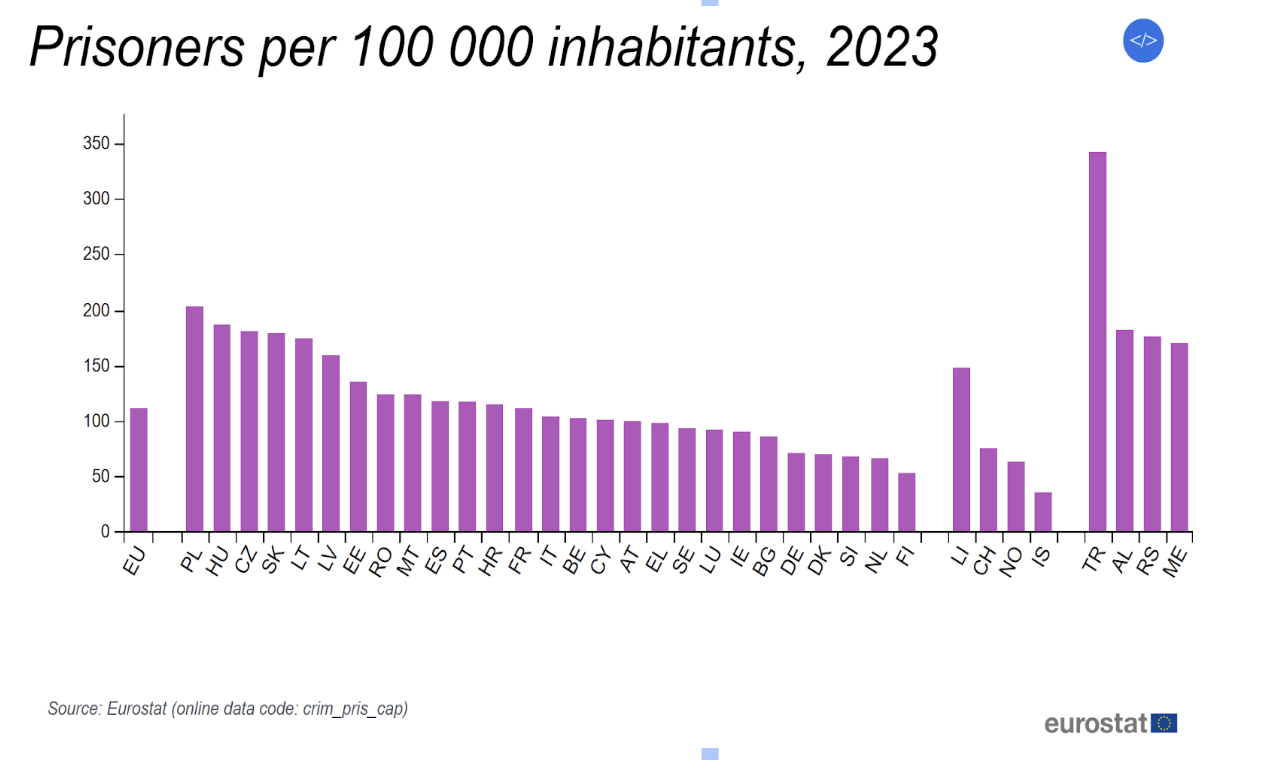

What may be surprising is that there is a total absence of a positive correlation between the incarceration rate and prison occupancy rate in the surveyed countries. Cyprus, with by far the worst prison overcrowding crisis in Europe, had an incarceration rate of just 101 (per 100,000 citizens) in 2023. This was well below the EU average of 110 and positioned it on the lower side of the distribution relative to the mode, as seen below.

In that same year, Poland had the highest incarceration rate in the EU with 203 prisoners for every 100,000 inhabitants. However, their occupancy rate was only 84.7%, well below the EU average of 94.6%, suggesting a comfortable margin of available capacity despite a comparatively large prison population. These examples have come from the statistical extremes, yet a cursory comparison of the below graphs will demonstrate that incarceration rates and occupancy levels do not necessarily move together, and that countries with similar incarceration profiles can nonetheless experience markedly different levels of prison overcrowding. In fact as my graph below proves*, these two variables are negatively correlated.

With this in mind, the comment by Ireland’s Chief Inspector of prisons, that “No comparable jurisdiction has ever succeeded in building itself out of overcrowding," is only the more baffling. Suppose the Chief Inspector believes the expansion of prison capacity cannot reduce occupancy rates. In that case, he must be of the view that only a policy of systematic, premature release of prisoners can solve the overcrowding crisis. Most of his European colleagues seem to agree. Last September almost 140 prisoners were released early to ease overcrowding in Belgian prisons. In the Netherlands a blanket two-weeks was taken off virtually every prisoner's sentence because of the cell shortage. In France (as well as Great Britain) offenders may apply for early release after having completed just half of their sentence. For repeat offenders this is raised to two-thirds. Ireland, an outlier even in Europe, grants prisoners automatic and unconditional release after having completed three-quarters of their sentence, regardless of their behaviour inside. This threshold is regularly reduced to two-thirds for those in training or rehabilitation programs, nevertheless the severity of the crisis appears to be worsening rather than abating: "Prison overcrowding is leading penitentiary establishments to a breaking point," warned the congress of the French National Union of Penitentiary Directors (SNDP) in a statement. They continued to say that "today we are returning to society people who are potentially more dangerous than on the day they were incarcerated,". From the union which represents directors of prisons and penitentiary services for integration and probation across France it is not a warning to be taken lightly.

The effectiveness of this policy can be seen by a glance at the prison overcrowding statistics published since the most recent Eurostat report, which I have used for all my mentioneabove the above mentioned figures. Whereas in 2023, Ireland had a prison occupancy rate of 104.8%, the average rate of overcrowding across the country's 14 prisons is now 121% with both female prisons in Dublin and Limerick operating at over 150% capacity and every closed prison in the country now considered overcrowded. In France where Eurostat reported an occupancy rate of 122.9% in 2023, as of May 1, 2025, 83,681 people were detained for 62,570 places, representing an overall prison occupancy rate of 133.7%, according to figures from the Ministry of Justice. Belgian prisons held 12,353 inmates on the 20th September 2024 whilst there was space for 11,010. In a report by Belgian public broadcaster VRT only two weeks ago a prison officer stated there were now 13,414 inmates for only 11,098 places and in her own prison of Mechelen 157 prisoners were crammed into cells designed for 84. 1061 more inmates but 88 new places. This equates to an occupancy rate of 120.9% or a 7.7% increase compared to 2023.

What can governments do?

So if early release jeopardises public safety without any durable effect on the growing overcrowding crisis why do governments continue to resort to it? The answer is they have no other choice. In Ireland, the General Secretary of the Prison Officers Association has warned that “even if all 1,500 new spaces due to be completed in 2031 were provided tomorrow, the prisons would still be overcrowded.” and a similar story unravels across Europe. Prison officers are being given ever-increasing workloads yet their resources remain the same and new capacity cannot keep up with the demand for cells. The results are a worsening of conditions for staff and prisoners alike as in Mechelen where the prisoners previously had fitness, Dutch lessons and library time outside of their cell. Due to staff shortages these have all been cancelled and replaced with 23 hours per day behind bars. Even in the case of serious disturbances or fights in cells, as one prison officer explains, wardens do not dare enter the overcrowded cells where they would be quickly overpowered by five male prisoners. The six or seven staff necessary to enter are simply not available all at one time at one place.

But if early release programs are a necessary emergency measure to ease dangerous overcrowding in the short term they do not work long term and governments will eventually be forced to seek out more sustainable solutions. What might these be? The first is obvious, building more capacity, more quickly. Yet even if the relevant difficulties with national planning regimes were overcome - an unlikely prospect - improvement would not be seen until the medium term; many years at the very earliest.

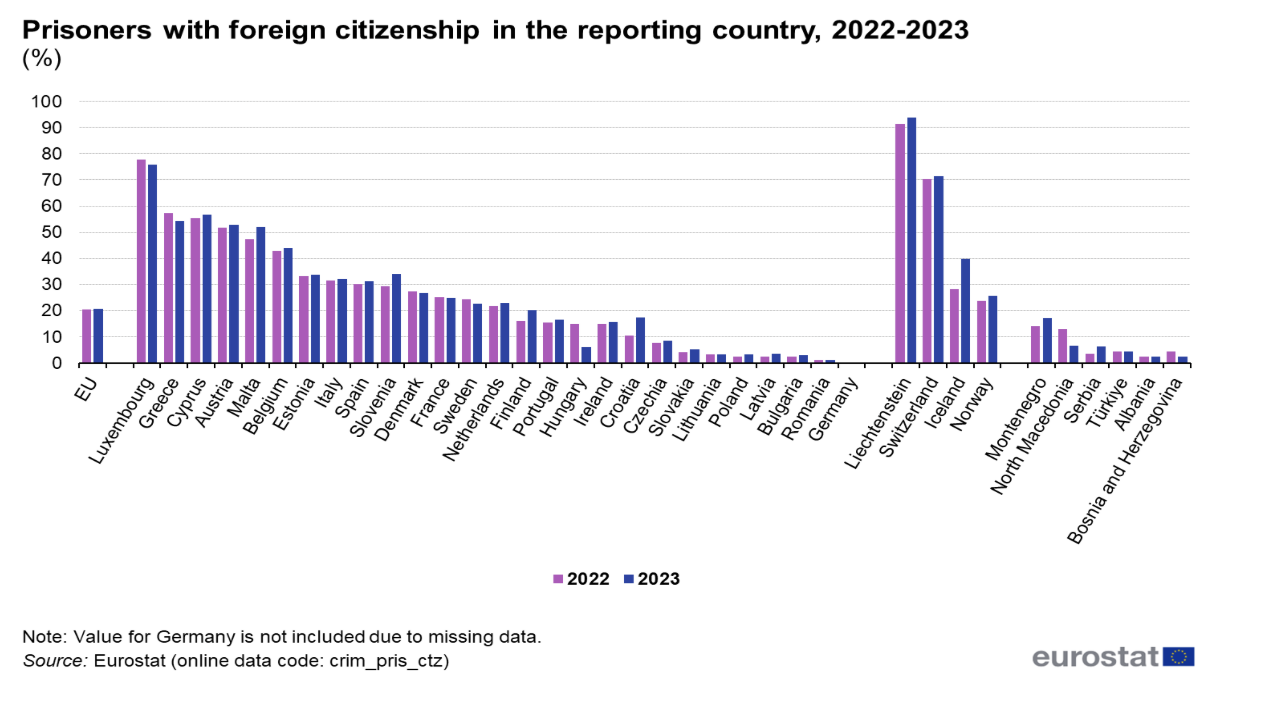

The second arises from another startling statistic from the Eurostat data, that in ten member states foreign citizens made up more than 20% of prisoners and in many including Austria, Greece and Cyprus it was more than half. A recent report from the Netherlands found that 10% of all prisoners in Dutch jails are foreign citizens with no right to be in the country whatsoever. Previously, bilateral agreements such as that which existed between Belgium and the Netherlands allowed Dutch suspects to extradited to face punishment in Belgium and vice versa. However a series of judicial decisions in the Netherlands, which found the overcrowding crisis in Belgian prisons to be so serious that extradition would violate suspects human rights has caused the agreement to collapse. Closer intergovernmental co-operation at both a European and global level including extradition and repatriation agreements could lead to a more equitable distribution of prisoners amongst member states, alleviating the burden on those most affected by the crisis. This would improve conditions for prisoners and prison staff alike and grant much-needed breathing space to prisons nearing their breaking point. No matter what policies EU governments ultimately pursue, it is clear that only a combination of expanded capacity, coordinated international cooperation, and a decisive break from short-term crisis management will begin to reverse the trajectory of Europe’s overcrowded prisons.