The Carbonara Scandal: Italian overreaction or a real problem of food counterfeiting?

By Aurora Dagnino, Reading time: 5 minutes

Carbonara Pasta Immagini di Carbonara | Scarica immagini gratuite su Unsplash

Pizza, pasta, lasagna ....everyone loves Italian food! Indeed, Italians are so deeply proud of their culinary traditions that they have even sought recognition of Italian cuisine as Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. As an Italian, I have to admit we can get quite defensive when someone unintentionally ‘offends’ our cuisine by reproducing it the wrong way. Italy’s Minister of Agriculture, Francesco Lollobrigida, clearly felt the same when he discovered Delhaize’s so-called ‘carbonara sauce’ being sold inside the European Parliament in Brussels, calling it ‘unacceptable’. Delhaize's version contains cream and pancetta, which are not included in the traditional recipe from Rome.

The jar of carbonara sauce made by Belgian company Delhaize- CNN ‘Fake’ carbonara sauce causes outrage in Italy | CNN

However, while Italians' culinary indignation can often be a source of fun, there are some more serious issues at play.

Italy’s biggest agribusiness association, Coldiretti, said that the "scandal of fake Italian products" cost the country €120 billion a year. According to the association, the use of the Italian flag colors, invented Italian sounding product names and even photos of Italian monuments amounts to misleading representations under European Union regulations.

However, it is worth noting that the biggest amount of counterfeit Italian products are sold not in Europe, but in the United States, South American countries and Australia. This is largely because the European Union has established a strong regulatory system that protects the authenticity and reputation of traditional agri-food products.Through geographical indications (PDO/PGI) and a growing body of CJEU case law, the EU offers a stronger protection than other jurisdictions.

Geographical indications establish intellectual property rights for specific products, whose qualities are specifically linked to the area of production.

Geographical indications comprise:

PDO: protected designation of origin (food and wine)

PGI: protected geographical indication (food and wine)

GI: geographical indication (spirit drinks).

Protected designation of origin (PDO)

For a product to be registered as PDO, all stages of the production must be carried out in the specific region. For example,the Kalamata olive oil PDO is entirely produced in the region of Kalamata in Greece, using olive varieties from that area.

Protected geographical indication (PGI)

For a product to be registered as PGI, at least one of the stages of production must take place in the region. For example, the Westfälischer Knochenschinken PGI ham is produced in Westphalia using age-old techniques, but the meat used does not exclusively come from animals born and reared in that specific region of Germany.

Geographical indication (GI)

GI protects the name of a spirit drink that comes from a specific country, region, or locality, where its distinctive quality is closely linked to its geographical origin.

To be registered as GI, at least one stage of distillation or production must occur within the designated region, although the raw ingredients do not necessarily have to originate there.

For example, the Irish Whiskey is a recognised GI that is distilled and matured in Ireland, even though not all the raw materials used comes exclusively from Ireland.

Nonetheless, the EU has not stopped there; through its case law, it has developed the prohibition of the notion of evocation.

Evocation occurs when a product, even without directly using the protected name, creates in the mind of the average consumer a “sufficiently clear and direct link” with the registered PDO or PGI. The key idea is that a producer must not exploit the reputation of a protected product.

Origins and development of the doctrine

In C-87/97, Gorgonzola / Cambozola, the Court held that the partial incorporation of a protected name into another name could constitute evocation. Here, the mere presence of the word “-zola” in “Cambozola” was considered enough to create a mental link with the famous Gorgonzola cheese.

Gorgonzola Cheese PDO, Gorgonzola Cheese P.D.O. - Dop Italian Food

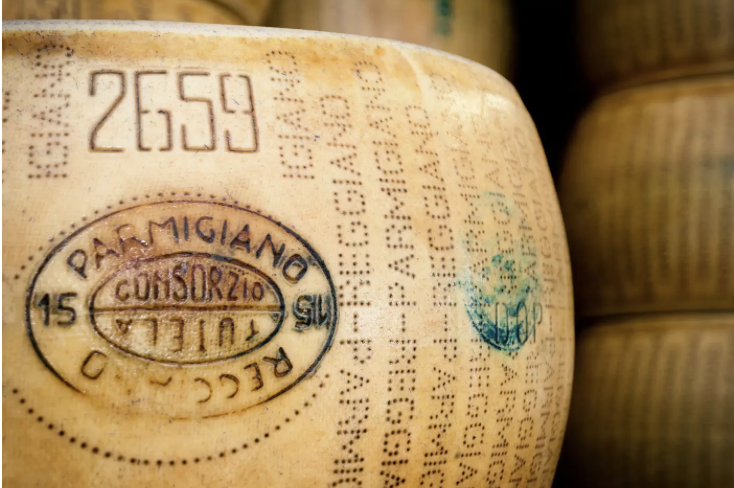

Subsequently, in C-132/05, Parmigiano Reggiano / Parmesan, the Court expanded the concept by stating that evocation of a PDO can arise even without phonetic or visual similarity. Germany was selling a type of cheeses labelled “Parmesan,” claiming the term was generic, but the Court held that “Parmesan” was conceptually linked to the PDO Parmigiano Reggiano. Because the use of the word “Parmesan” could trigger in the consumer’s mind an image of the characteristics and reputation of the PDO Italian cheese, Germany was found in violation of EU Geographical Indications rules.

Parmigiano Reggiano Cheese PDO, Cosa significa Parmigiano Reggiano DOP? – Spadarotta

In C-614/17, Queso Manchego, the Court held that packaging showing images associated with “La Mancha”, for example Don Quixote-style characters, could mislead consumers by creating a mental association with the PDO “Queso Manchego,” even though the name “Manchego” was not used.

The reasoning of the CJEU was that evocation can operate beyond words: symbols and illustrations can generate the same effect.

Queso Manchego cheese PDO, El verdadero queso manchego - GRUPO NOVELDA

More recently, the General Court in T-406/24, PriSecco / Prosecco confirmed its expanding doctrine.

This case is the latest illustration of how strictly EU courts continue to apply Geographical Indications protection. The Court invalidated the trademark Prisecco because the term sounded similar to “Prosecco,” and thus could evoke the Italian PDO in the mind of consumers, even though the contested product was a non-alcoholic fruit beverage.

Prosecco Wine PDO Le qualità uniche dell'uva Glera nella produzione del Prosecco

These cases demonstrate that the concept of evocation has become increasingly protective and expansive. It now includes a wide range of marketing strategies, from names to symbols and to packaging design, that could allow producers to take advantage of and exploit the cultural, gastronomic, or reputational value of a protected product.

It would be no surprise if the Court, in a future case, decided to expand this doctrine even to non-PDO products, especially if Italian cuisine were to become recognised as world cultural heritage.

Therefore, even though Italians sometimes exaggerate and treat their typical dishes as if they were their own children, counterfeiting products and misleading consumers remains a crucial issue that undermines cultural identity.