From Baltic Stability to Democratic Backsliding? The Threat of Latvia’s Istanbul Convention Withdrawal in Regional Perspective

By: Nikola Kirkov

Reading time: 6 minutes

Latvia’s political landscape has been thrown into turmoil after a controversial parliamentary vote to withdraw from the Istanbul Convention sparked widespread protests and fears of democratic backsliding. As public demonstrations intensify and European partners express mounting concern, the furore has become a defining litmus test for Latvia’s commitment to human rights and EU values.

The Istanbul Convention defines violence against women as a violation of human rights. (Evika Siliņa via X)

Protests, Petitions, and a Political Reckoning

For the past weeks, Latvia has found itself in the middle of political instability, spurred by the controversial parliamentary vote on October 31 to withdraw from the Istanbul Convention, a human rights convention aimed at tackling domestic abuse and standardising support for women facing violence. The threat of human rights backsliding in the country caused a staggering wave of protests, with the biggest one being the ‘Let's Protect Mother Latvia’ protest in Riga. The NGO-organised rally was attended by approximately 10,000 people, with demonstrators gathering in the heart of the capital to demand the immediate termination of any legislative initiatives that would compromise Latvians’ human rights in the name of political tactics.

Alongside public demonstrations, more than 65,000 people have signed an initiative on the "Manabalss.lv" portal, the fastest-growing petition in the platform’s history. The petition calls on the President of Latvia and Parliament (Saeima) to reject any proposals that would facilitate Latvia’s withdrawal from the Convention.

Slogans such as ‘Wife-beating is not our value’ and ‘Latvia is not Russia’ reflect how, ever since Russia waged its illegal full-scale invasion against Ukraine in 2022, Latvian society has become acutely alert to any sign of the country drifting toward Moscow, including votes against key treaties safeguarding human rights – a move more reminiscent of authoritarian-leaning states. With the protest marking the biggest civil demonstration Latvia has seen in several years, a clear message is being sent out to politicians who actively try to consolidate as much power as possible before the upcoming elections Latvia will be heading off to in 2026.

Protesters at a demonstration demanding accountability after a woman's murder in Riga, Latvia (Gints Ivuskans/DeFodi Images via Getty Images)

Domestic Dimension Behind the Issue

The Latvian parliament voted on 31 October to withdraw from the Istanbul Convention, with 56 voting in favour of leaving the treaty and 32 voting to stay. The vote would have effectively made Latvia the first EU Member State to opt out of the international human rights treaty, which the very same parliament ratified in November 2024.

The motion required the signature of Latvian President Edgars Rinkevics, who has indicated he is not in favour of the political move. The President criticised the legislation, claiming that it would send a ‘contradictory message’ regarding the country’s international obligations to both Latvian society and allies of the Baltic country.

While the decision came as a shock to the European partners of Latvia, tension regarding the Convention has long been brewing in the country, with opposition right-wing politicians starting the process earlier in September by raising arguments regarding the treaty promoting ‘gender ideology’ and harming children. The consequent support from the Union of Greens and Farmers (ZZS) party, an agrarian political alliance which is a part of the governing coalition ruled by the current Prime Minister of the country secured the necessary majority for adopting the initiative. The disagreement within the governing coalition signals major cracks in the stability of the ruling alliance ahead of the 2026 elections but also points towards the worrying tendency of Eastern European countries drifting towards policies of an authoritarian nature, which go against democratic values and the rule of law. Additionally, the backlash has exposed the governing coalition as effectively non-functional, with parties prioritising retaliation over governance.

Latvian Parliament votes to opt out of the Istanbul Convention. (Copyright AP Photo)

The leader of the opposition right-wing party, Latvia First, which put forward the initiative, Latvian oligarch Ainārs Šlesers, has found himself in the middle of controversy many times due to business ties to Kremlin-affiliated Russian oligarchs. The political move, framed as an act of ‘populism’, was fiercely backed by right-wing politicians, arguing that the Convention provides for ‘social gender’ and embodies a ‘foreign ideology creeping into our everyday lives.’ MPs in favour of the withdrawal framed the Convention as an ideological, “neo-communist” document promoting gender reassignment and the destruction of Latvian traditional values, while also insisting that national law measures on the protection against violence and domestic abuse are solely sufficient and the Convention is ineffective. Latvia has a longstanding problem with high levels of domestic violence.

These talking points have served as the opposition’s logical backbone of their campaign, even though the Council of Europe has repeatedly disproven such claims, notably stating in 2022 that ‘the Istanbul Convention does not establish any new norms on gender identity or sexual orientation.’ The political weaponisation of the human rights treaty has not occurred in a vacuum – the decision has been accompanied by a recent proposed amendment that would restrict abortion access in Latvia.

New Unity (JV), the party which brought about the ratification of the Convention in 2024, and The Progressives argued in Parliament that withdrawing from the Istanbul Convention would damage Latvia’s reputation, weaken efforts to combat violence against women, and align the country with Russian propaganda narratives.

Due to the multifaceted essence of the withdrawal and the dangerous signal it would send to Europe, President Rinkēvičs refused to sign off on the parliamentary initiative, leading to lawmakers agreeing to postpone the new vote on the matter until after next year’s parliamentary elections. The vote is now scheduled for November 1, 2026, while the elections will be held no later than October 3. Prime Minister Siliņa celebrated the postponement, declaring it ‘a victory of democracy, rule of law, and women’s rights’, which affirms Latvia’s commitment to ‘European values’.

The Istanbul Convention

The Istanbul Convention, adopted by the Council of Europe Committee of Ministers on 11 May 2011, is the first European treaty specifically targeting violence against women, aimed at standardising minimum support on prevention, protection, prosecution, and the development of policies countering violence. The EU as a whole acceded to the Istanbul Convention in 2023, making it a legally binding agreement for the 27 Member States in areas falling under EU competence, including EU institutions, public administration, judicial cooperation in fighting crime, and asylum rights.

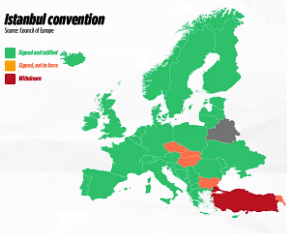

Despite this, several EU Member States, such as Bulgaria, Hungary, Slovakia, Czechia, and Lithuania, have not yet ratified the Convention on several grounds, mainly the legislation’s incompatibility with national ‘traditional’ values. The only country to ever opt out of the Istanbul Convention is Türkiye. The increasingly authoritarian country chose to withdraw from the Treaty in 2021, sparking EU condemnation.

In Latvia, the Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence entered into force on 1 May 2024. If the delayed parliamentary decision to withdraw from the treaty would effectively make Latvia the first EU Member State to do so. Despite talking points hyper-fixating on ‘gender ideology’ from the right-wing political sphere, thanks to the Convention, Latvia has managed to criminalise sexual abuse, alongside other significant policies providing relief and assistance to victims of sexual misconduct.

EU countries in the Istanbul Convention. (via Euronews)

International Response & External Implications

The Latvian parliamentary decision has generated strong condemnation from EU institutions, international organisations, and neighbouring States, raising concerns about the country’s human rights trajectory and its standing within Europe. Amnesty International warned that the withdrawal would be ‘a devastating blow’ to women’s rights, emboldening perpetrators and signalling impunity for gender-based violence, urging President Edgars Rinkēvičs to veto the bill and resist the influence of ‘anti-rights groups spreading harmful disinformation’. The European Commission similarly stressed that, no matter the decision, Latvia would still remain bound by international standards on protecting women, despite attempts at democratic backsliding.

António COSTA (President of the European Council), Evika SILIŅA (Prime Minister, Latvia). (Source: Consilium Europa)

The reaction among Baltic neighbours has been distinctively sharp. Lithuanian human rights experts cautioned that Latvia risks setting a regional precedent akin to Hungary’s democratic erosion, undermining shared human rights standards and encouraging harmful Russian-influenced narratives across the region. Lithuania’s Prime Minister reiterated her government’s intention to ratify the Convention, emphasising its importance for international credibility. Estonia, an EU Member State where the Convention has been enforced since 2017, issued its strongest criticism, yet with Prime Minister Kristen Mihal denouncing Latvia’s decision as disregarding women’s safety and ‘moving in the wrong direction’.

European legal and diplomatic actors also voiced alarm. EU General Court judge Inga Reine warned that the withdrawal creates a ‘negative presumption’ against Latvia and jeopardises cooperation. The Council of Europe called the decision a ‘dangerous message’ in the midst of protests in Riga and across Europe and North America, led by the Latvian diaspora.

Broadly speaking, Latvia now faces the risk of alignment with Türkiye - the only other state to leave the Convention. This position would inevitably undermine the country’s previously strong Nordic-Baltic human rights reputation. Foreign investors, universities, and ambassadors from 15 countries have warned that the withdrawal could damage Latvia’s investment climate, global image, and credibility as a rights-respecting democracy.

Protesters at a demonstration against the withdrawal from the Istanbul Convention (E. Blažys via LRT)

The dispute surrounding Latvia’s withdrawal from the Istanbul Convention has exposed the depth of the country’s political fragmentation and the consequences this holds for its regional standing. As the 2026 elections approach, Latvia’s political sphere faces a pivotal choice between reaffirming democratic commitments or allowing further drift toward isolationism within Europe.